In the US, non-medical use of prescription drugs is second only to marijuana. Marc Buhagiar meets up with Prof. Marilyn Clark to investigate just how dangerous this problem is around Europe. Illustrations by Sonya Hallett

Recently, Jane has been having problems sleeping. At work she is getting frustrated because she has been up all night and cannot focus. Jane speaks to her friend Sarah about her sleeping problems. Sarah, who is also an insomniac, gives Jane some sleeping pills that her doctor prescribed so Jane can finally sleep. Jane and Sarah are not real people, but this seemingly harmless action of a friend giving another friend prescription medication is a common phenomenon and can lead to many problems and complications. Prof. Marilyn Clark, a professor at the Faculty for Social Wellbeing (University of Malta), has coordinated research on the gender dimension of non-medical use of prescription drugs around Europe and the Mediterranean for the Pompidou Group, the drug policy arm of the Council of Europe. The research project collected data from 17 countries, including Malta, to explore gender and the non-medical use of prescription drugs.

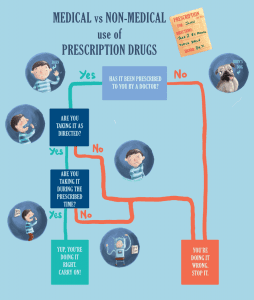

‘Essentially, this is a phenomenon which is becoming increasingly problematic all over the world. The drug field has, up till recently, focused primarily on illicit substances as well as alcohol and tobacco, but has somewhat neglected the use of prescription medications,’ she explains. But what exactly is meant by non-medical use of prescription drugs? The Pompidou Group has adopted the definition developed by the Lithuanian Presidency of the Council of Europe in 2013 which defines it as the ‘use of a prescription drug, whether obtained by prescription or otherwise, other than in the manner or for the time period prescribed, or by a person for whom the drug was not prescribed.’ A doctor might have originally prescribed you the drug, but you might use it not as directed or for longer periods then directed. Clark explains there are a number of motivations and reasons for this.

‘Essentially, this is a phenomenon which is becoming increasingly problematic all over the world. The drug field has, up till recently, focused primarily on illicit substances as well as alcohol and tobacco, but has somewhat neglected the use of prescription medications,’ she explains. But what exactly is meant by non-medical use of prescription drugs? The Pompidou Group has adopted the definition developed by the Lithuanian Presidency of the Council of Europe in 2013 which defines it as the ‘use of a prescription drug, whether obtained by prescription or otherwise, other than in the manner or for the time period prescribed, or by a person for whom the drug was not prescribed.’ A doctor might have originally prescribed you the drug, but you might use it not as directed or for longer periods then directed. Clark explains there are a number of motivations and reasons for this.

‘You might be using the drugs in a way that’s different. For example, the doctor advises you to take one before you sleep and you take three in the morning crushed with a glass of whisky. Or else, you’re using them and they’ve never come to you from a doctor, or you’re using them specifically to get high.’

The Pompidou Group study is concerned with the use of psychotropic substances (chemicals that change brain function) namely opioids, central nervous system depressants, and central nervous system stimulants. But how can these drugs be dangerous if a doctor prescribes them?

The effects of illicit substances such as heroin and cocaine are well known and most people know to steer clear of them because of the adverse effects these substances have on the body. However, people seem to underestimate the potentially lethal side effects of prescription drugs, simply on the basis that they are found in pharmacies. ‘People think “Oh ok, it’s a prescription medication, then it shouldn’t be so harmful’,” Clark explains. They also fail to see that certain prescription drugs also have a lot in common with their illicit counterparts. ‘Prescription medications are essentially, in their chemical composition and in their psychotropic effects, not radically different from illicit drugs. They may be a synthetic or semi-synthetic version of the natural substance that comes prescribed by a doctor, but that also lends them to use that is not medically prescribed because they have sought- after psychotropic effects. Today, drugs which are very powerful, such as Oxycontin (a narcotic analgesic) can be obtained legally from a doctor or illegally from the street, from your dealer,’ she adds.

In the United States of America, this phenomenon is well documented and it seems that the use of prescription drugs without a doctor’s guidance seems to be alarmingly widespread. What the Pompidou Group is trying to achieve is to provide a snapshot of this phenomenon around the European-Mediterranean regions to see how policy can be formed regarding the non-medical use of prescription drugs with a specific emphasis on gender. Clark explains that in the United States, the non-medical use of prescription drugs is second only to marijuana in terms of prevalence, outranking hard drugs such as heroin and cocaine which have garnered a bad reputation. What is worrying is that certain prescription medication can be just as strong as heroin and cocaine. According to NIDA (the National Institute of Drug Abuse), opioid related overdose deaths have quadrupled in the United States since 1999 and, by 2007, outnumbered overdoses involving heroin and cocaine.

Whereas the USA has a clear indication of what is happening with prescription drug use, the same cannot be said for Europe. ‘We wanted to see what monitoring practices were in place in the European countries because to know the extent of the problem, you need a very good monitoring system—you have to measure the phenomenon to be able to say that it is a problem. While the United States has a number of states, it is made up like one country, and they have one particular monitoring system, they define it in one way.’ This is not the case in Europe as different countries have different legislative frameworks and consequently different prescribing and monitoring frameworks, which complicates things when it comes to collecting data.

The Gender Question

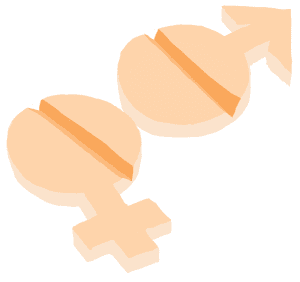

Who is at most risk? ‘Generally, it appears to be a bigger problem for women but it depends on the type of drug. Sedatives and tranquillisers appear to be more popular amongst women while amphetamine use is more popular amongst men, especially younger men,’ according to Clark. The American research and the European data show that there are big differences with prescription drug use when it comes to gender, which is why the Pompidou Group is focusing on the gender dimension.

Why are women more at risk? ‘Women are more likely to be prescribed sedatives and tranquillisers than men are because, perhaps, it’s more culturally acceptable,’ explains Clark. Women seem to live much more stressful lives as they juggle childcare and career. Prescription drugs seem to be popular amongst women because their use is much more socially acceptable. They are less likely to be prosecuted for taking a prescription pill over heroin, which means non-medical use is harder to curtail. According to Clark, women seem to face more backlash for using illicit drugs over men because of societal norms. Prescription medication

is also much easier to acquire than illicit drugs.

“Prescription medications are essentially, in their chemical composition and in their psychotropic effects, not radically different from illicit drugs”

According to Clark, women also tend to enter their drug using career later in life, but reach the level of dependence much quicker. This has been termed the ‘telescopic phenomenon’ and means that the window for intervention is shorter for women. ‘Prescription drug use amongst women increases with age. It goes up steadily and then it drastically increases in their 30s and mid-life,’ she adds. The available data indicates that trauma from sexual abuse and interpersonal violence is a main contributor to the use of non-medical drugs for women. In fact, women seem to favour central nervous system depressants such as Valium and Xanax which calm and relax users.

Women do not seek professional help as much as men do when it comes to drug use, which is why the Pompidou’s research project is also making recommendations to update policy to prevent and treat users. ‘They don’t go for treatment because women’s lives present a lot of barriers to treatment. Especially if you’re a mum and have children, if you present for treatment you’re opening yourself up to a lot of enquiry and a lot of potential labelling and stigmatisation with the constant fear that “being an addict equals not being a good mum hence my children might be taken away”,’ she explains.

According to Clark, treatment also seems to be very male-oriented. The trend seems to be that most illicit drug and alcohol abuse happens amongst men. However, when it comes to prescription drugs, females register a higher use. This is something new to the drug field and awareness that women require specialised treatment services has only emerged since the late 1970s. Before that, usually only men sought treatment, perhaps because of social constraints imposed on women. Another possibility is that women might need their children with them when tackling their problem, or that they do not wish to seek treatment in the company of males, especially if the non-medical use of drugs was triggered by sexual abuse by men.

Although gender plays a pivotal role in determining who is mostly at risk of using prescription drugs without medical guidance, it is not the only factor. Other issues also intersect with gender such as age, class, employment, marital status, occupation, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. According to Clark, our local gender dimension is very well developed. ‘We have specific women’s clinics and we have a shelter that’s specifically for women,’ she said.

Chronic pain patients seem to be at risk of abusing prescription drugs because of the opioids they take to help soothe pain. When drugs such as Oxycontin, an opioid which can be swallowed, injected or crushed, are taken in the absence of pain, they register pleasurable effects in the brain which might lead to addiction. People who suffer from emotional pain might become dependent on central nervous system depressants which take the form of sleeping medication and anti-anxiety medication. People of different age groups are also susceptible to abusing prescription medication. These would include the elderly who are prescribed a multiplicity of prescription drugs, or highly stressed adolescents who take central nervous stimulants (ADHD and hyperactivity prescription medicine). ‘They can be abused for cognitive enhancements, so you’ve got an exam and you want to stay up to study and you need to be sharp; or you’ve partied all night and you have something to do which requires focus,’ Clark explains. Problem drug users also use prescription drugs to complement their daily use of illicit substances and people with mental health difficulties are also at risk as they are prescribed a number of central nervous system medications. Finally, health care professionals might also use prescription drugs non-medically as a form of self-treatment to cope with a multiplicity of problems such as stress, depression, and anxiety, to mention but a few.

Chronic pain patients seem to be at risk of abusing prescription drugs because of the opioids they take to help soothe pain. When drugs such as Oxycontin, an opioid which can be swallowed, injected or crushed, are taken in the absence of pain, they register pleasurable effects in the brain which might lead to addiction. People who suffer from emotional pain might become dependent on central nervous system depressants which take the form of sleeping medication and anti-anxiety medication. People of different age groups are also susceptible to abusing prescription medication. These would include the elderly who are prescribed a multiplicity of prescription drugs, or highly stressed adolescents who take central nervous stimulants (ADHD and hyperactivity prescription medicine). ‘They can be abused for cognitive enhancements, so you’ve got an exam and you want to stay up to study and you need to be sharp; or you’ve partied all night and you have something to do which requires focus,’ Clark explains. Problem drug users also use prescription drugs to complement their daily use of illicit substances and people with mental health difficulties are also at risk as they are prescribed a number of central nervous system medications. Finally, health care professionals might also use prescription drugs non-medically as a form of self-treatment to cope with a multiplicity of problems such as stress, depression, and anxiety, to mention but a few.

The Pompidou Group’s main challenge was collecting all the data from different countries and analysing it. Data for legitimate psychotropic prescription drug use was easy to gather and higher rates are registered for females in most of the countries surveyed. The data on the non-medical use of prescription drugs has a number of gaps. In Greece and Lithuania females register higher levels of use, which is not seen in Lebanon and Israel. Additionally, in Germany and Serbia, psychotropic fatal overdoses are higher for females than for males. The differences observed in the use of prescription drugs are not enough for clear documentation as comparisons cannot be easily made since there is no standard reporting system in Europe and the Mediterranean. Another problematic factor arises when General National Surveys do not clearly differentiate between ‘medical use’ of prescription drugs and ‘non-medical use’. ‘The study clearly indicates that we need to have a monitoring system that is the same for the whole of Europe so that we can make comparisons. There’s been a different measuring rod for you and a different measuring rod for me. This was the biggest problem that we encountered,’ Clark explains.

“Politicians and policy makers need to be aware that the problem exists and that they need to cater for it”

On the other hand, with ESPAD (the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs), which surveys 16-year-old children, respondents are specifically asked if they have used prescription drugs without a doctor’s consent. It asks about sedatives and tranquillisers: females use them twice as much as males.

Alarmingly, policy makers have not prioritised non-medical use of prescription drugs. ‘Politicians and policy makers need to be aware that the problem exists and that they need to cater for it.’ Without the right policies the problem cannot be tackled effectively.

This type of drug use is gaining momentum around the world. Policy makers need to be sensitive towards the different treatments needed to curb people’s addictions. ‘The misconception that prescription drugs are not dangerous needs to change—just because a substance comes in a bottle with instructions, doesn’t mean that it is any less dangerous than a substance bought on the streets. Granted, prescription drugs can improve our health when used correctly, but can also destroy it when abused.’ •

Comments are closed for this article!