Science fiction reimagines our future. Sometimes it is inspired by science; sometimes it inspires current scientists. Anna Fava visited Prof. Victor Grech at his home to talk about the mythology of science fiction and his love for Star Trek.

“All children mythologise their birth. It is a universal trait. You want to know someone? Heart, mind and soul? Ask him to tell you about when he was born. What you get will not be the truth: it will be a story. And nothing is more telling than a story.”

[The Thirteenth Tale, Diane Setterfield]

Science fiction is a genre of scientific chronicles, which often occur in diverse time frames other than that contemporary. It is the blending of scientific principles and fantasy, exploring potential outcomes of technological innovations.

Science fiction is a genre of scientific chronicles, which often occur in diverse time frames other than that contemporary. It is the blending of scientific principles and fantasy, exploring potential outcomes of technological innovations.

In archaic cultures, mysterious phenomena are often attributed to the supernatural and spiritual. Through magical tales and sacred rituals, primitive communities explore the relation between experiences and dreams, an archetype of human visions and aspirations. One Aztec legend speaks of the deity Quetzalcoatl, whose human figure traversing on barren land would have starved to death if not for a passing rabbit. The rabbit offered its life to save him and Quetzalcoatl was so moved that he imprinted the rabbit’s image in the moon’s light—the rabbit moon folk-tale was born.

Other mythologies simply invented creatures like the unicorn as a creative product of the human imagination. In a similar vein, primeval cultures invented myths to explain phenomena they had no hope of understanding. The Chinese thought that the goddess Xi He carried one of her ten sons across the sky. Each of them was a sun. Science fiction, which uses the human imagination to explore our future, also tries to understand its uncertainty by creating stories. Doubt about future events led to an instinctive need to try and control this unexplainable world. Take the traditional rain dance of the Aborigines. Such superstitions have no origin whatsoever in experimental data. On the contrary, science fiction tends to stem from established scientific fact. To better understand science fiction, I met Prof. Victor Grech a cardiac paediatrician with a Ph.D. in science fiction, who also co-organised a local Star Trek symposium.

Prof. Grech explained how science fiction gave a paradigm shift to the world of ancient mythology. In the modern world humans have expanded their knowledge of how the world works through scientific and logical inquiry. Science fiction evolved as a plausible science chronicle.

Darko Suvin, a science fiction critic, defines the science fiction genre as ‘the literature of cognitive estrangement’ since it attempts to obtain certain legitimacy by appearing scientific. Science fiction posits the introduction of a novum (new idea) of a scientific nature, mostly through technological innovations like teleportation (instantaneous matter transport). This is because science fiction tends to be futuristic. Authors design innovative machinery and pioneering theoretical concepts, sometimes before scientists confirm them. This spawns a generation of new terminology to express innovation, such as playwright Karel Čapek coining the term robot in his play R.U.R. in 1920.

Science fiction writers attempt to envisage the future. They reflect upon patterns of love and death, aspiration, and reconciliation in a totally fresh context, by encouraging a sense of wonder and willing suspension of disbelief in the reader. In AD 190, Lucian of Samosata wrote the first science fiction story where the protagonists take a trip to the moon, encountering alien creatures and getting embroiled in celestial warfare. Subsequently, there have been several texts and poems which incorporate this kind of technology and themes like flying machines, the quest for immortality, an alternate history of our planet, fantastic voyages in outer space, and time travel. These reflect the culture and scientific progress of the time. Victorian era writers, Wells and Verne, reflected the innovative machinery of the industrial revolution, while Abbott, in roughly the same period, reflected in Flatland on the latest ideas exploring extra dimensions in space.

| A short Star Trek history |

|

In 1964, Gene Roddenberry already had plans for ‘a Western in outer space’ even though the first episode was not aired before 1966. Curiously, it was not well received when initially viewed but gained popularity through reruns. After three years of The Original Series, the Motion Picture production in 1979 helped the whole franchise bloom in popularity, gathering extensive fandom who were called ‘Trekkers’. The Next Generation episodes broadcast in the late 1980s, embraced more socially liberal morals than its progenitor, spawning two sequels (Deep Space 9 and Voyager) and four films. More recently, the series Enterprise and the two latest films continue to reach fans worldwide. In July 2014, Malta hosted the first academic Star Trek symposium. For two days, academics and fans discussed the philosophy, ethics, and scientific principles behind Star Trek. It intended to explore the boundaries of interdisciplinary research between the humanities, medicine, and the sciences in Star Trek. |

Star Trek fiction: myth and ethical principles

“Science fiction is metaphor. What sets it apart from older forms of fiction seems to be its use of new metaphors, drawn from certain great dominants of our contemporary life—science, all the sciences, and technology, and the relativistic and the historical outlook, among them.”

[Introduction to the Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin]

American screenwriter and producer Gene Roddenberry created the Star Trek series using ‘[his] social philosophy, racial philosophy, overview of life, and the human condition’, said Grech. Roddenberry thought that he would reach more people through media than any other conventional philosopher. By alluding to myth, enchantment, and logic, his philosophy of moral virtue is conveyed in over ten films and hundreds of TV series. The storyline reminds us of Aesop’s parables due to the inherent moral implications. These mostly emphasise dignity and respect for all sentient life, personal loyalty, tolerance of multicultural diversity (infinite diversity in infinite combinations), opting for peaceful resolutions rather than violent conflicts, and the exercising of our rational faculties and scientific knowledge to pursue truths, all the while advocating the importance of education and free thought. Star Trek encapsulates a Utopian future, one where the characters’ altruistic temperament matches Roddenberry’s belief in humanity’s potential for self-transcendence.

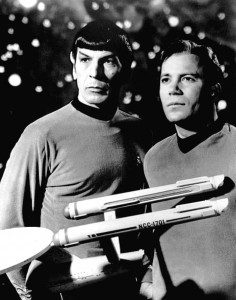

Grech explained how progressive these values were for their time. The series was launched on Thursday, September 8, 1966 with the Cold War, apartheid in the United States, and the influences of hippie culture in full swing. The spacecraft’s crew took in humans from all over the world (including a Russian, Japanese, and African-American woman), and science officer Spock, an alien from the planet Vulcan. These humanoid creatures are disciplined and logical. This is especially so for Spock, a member of this alien species who learned to master their emotions by following the teachings of Vulcan philosopher Surak, after their planet was almost destroyed by war. Star Trek exemplified diversity.

Victor’s research into science fiction Victor’s research into science fiction |

|

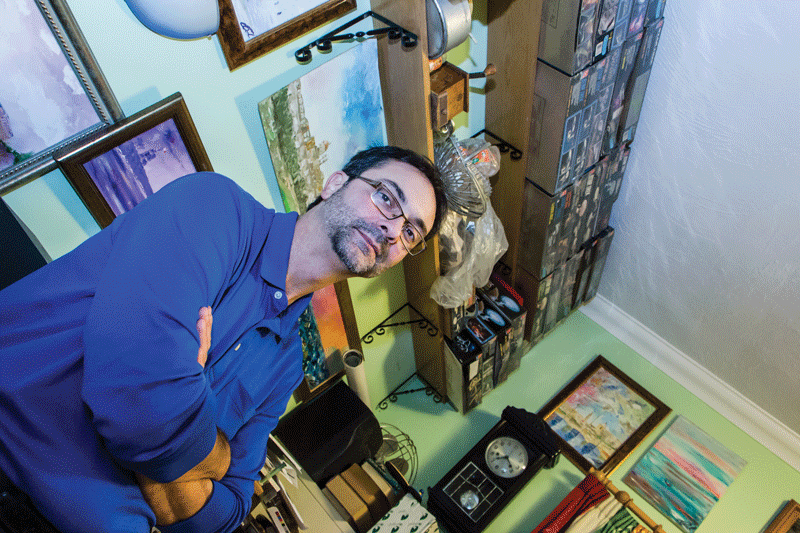

Prof. Victor Grech has been a science fiction fan from a young age. Although he studied medicine and became a paediatrician, he remains a physicist at heart, with an enduring interest in astronomy, astrophysics, and cosmology. The allure of science fiction eventually led to his reading for a Ph.D. called Infertility in Science Fiction at the Department of English, University of Malta. The thesis classified infertility in science fiction according to themes like after warfare, terrorism, state inflicted, alien inflicted, affecting aliens and animals. In over 300 texts one commonality ensued: optimism. Science Fiction is the modern replacement of the fairy tale and therefore almost always has a happy ending. Instead of monsters, we have aliens. Instead of magic, we find advanced technologies. The end result is the same, the willing suspension of disbelief and an abiding sense of wonder. The thesis spawned several scholarly (and otherwise) publications, with Star Trek offering the potential for lots more. Grech continues to read science fiction in his spare time and greatly enjoys watching science fiction films and series (such as Star Trek) with his two children who have also become fans. |

The Star Trek franchise incorporates several philosophical topics. The underlying ideology is humanistic: a secular approach that discards supernatural and religious dogma, replacing this with rationalism (where reason is the chief source of knowledge). Any deity or divine spirit is described as the myth of the past, discouraging any theistic worship.

Grech went on to describe how myth is explored in Star Trek. For example, in the curious episode Elaan of Troyius (view below), Captain Kirk encounters a mysterious yet conceited young princess whom he falls in love with because he has been affected by the biochemistry of her tears. In conventional alchemy these tears are a love potion, but modern science might slap on the chemical oxytocin, the so-called ‘cuddle hormone’ that seems to be linked to a person falling in love. ‘Add some technobabble, give it a chemical name’, Grech remarked jokingly about the validity of such aphrodisiacs. Reality is a lot more complicated.

Another episode Who mourns for Adonais? (view below) delves into ancient Greek beliefs, where Apollo has captured the Enterprise and demands worship from the trapped crew. As always, the Star Trek crew would contemplate the best logical solution to an otherwise labyrinthine problem, in this case by finding the source of Apollo’s power and rendering him vulnerable. As he fades with the wind to join his fellow brother and sister gods, he laments, ‘the time has passed. There is no room for gods.’ One can appreciate why postmodern civilisation in general dismisses these gods as mythology, and thus why myth is as evolving as language.

Speaking of language and communication, in The Next Generation, the episode Darmok (view below) portrays the difficulty of Captain Picard (of the Star Trek ship) to understand the Tamarian leader since his language cited metaphors derived from mythology and folklore. At the end of the episode, Picard remarks that ‘more familiarity with our own mythology might help us relate to theirs’ meaning that understanding our own stories more helps us communicate better with other societies. Indeed, science fiction is certainly more conscious and literary than primeval myth. Yet it is not designed to be the myth of society, but rather it is the mythology concocted for the delight of the technological human.

Fellow readers and fans, live long and prosper.

Find out more:

-

Grech, V. (2013). Philosophical Concepts in Star Trek: Using Star Trek as a curriculum guide introducing fans to the subject of Philosophy [online] James Gunn’s Ad Astra. Available at: http://adastra.ku.edu/philosophical-concepts-in-star-trek/ [Accessed 10 Oct. 2014].

-

Grech, V. (2013). The Pygmalion-Galatea myth in relation to simulation scenarios in Star Trek. Xjenza Online, [online] 1(2), pp.23-28. Available at: http://www.mcs.org.mt/index.php/xjenza/2013-vol-1-iss-2/114-xjenza-2013-2-03.

-

Star Trek: The Original Series, Elaan of Troyius [television series 3 episode 13]. (1968). [film] Hollywood: John Meredyth Lucas, Paramount.

-

Star Trek: The Original Series, Who Mourns for Adonais? [television series 2 episode 2]. (1967). [film] Hollywood: Gilbert Ralston, Gene L. Coon & Marc Daniels, Paramount.

-

Star Trek: The Next Generation, Darmok [television series 5 episode 2]. (1991). [DVD] Hollywood: Joe Menolsky, Phillip LaZebnik & Winrich Kolbe, Paramount.

-

Some other articles by Grech

Star Trek — Elaan of Troyius — Season 3, Episode 13

Star Trek — Who Mourns for Adonais? — Season 2, Episode 2

Star Trek — Darmok — Season 5, Episode 2

Star Trek The Next Generation Season 5 Episode… by mutterz

Comments are closed for this article!