A historical discovery does not always equal the unearthing of new documents or artefacts. Sometimes it’s about re-evaluating what we already know. Prof. Victor Mallia-Milanes tells Tuovi Mäkipere more.

The old adage goes; ‘History is written by the victors.’ As far as accuracy is concerned, stories from decades past should be taken with a grain of salt. Scribes’ biases need to be accounted for. Unless science develops a working time machine that will allow researchers to experience events first-hand, the past will have to be reconstructed through careful analysis of facts based on empirical evidence and their re-evaluation.

Prof. Victor Mallia-Milanes (Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Malta) believes that this ‘reconstruction’ can be made through various means, namely ‘the discovery of new facts, a new method of approach, a new interpretation of the significance of long-established facts, or a combination of them all.’ Questioning the traditional panorama, the established perception of the past, lies at the core of these efforts.

Mallia-Milanes exhibits his point with one of the most famous events in Maltese history—the Great Siege of 1565. With all the research conducted around the siege, it is hard to imagine what new information can be garnered without the use of the aforementioned time machine. Mallia-Milanes disagrees, in part. While there have been no new revelations or archival discoveries made in recent years, there is always the wider context to be taken into account when evaluating any phenomenon in history. The Great Siege is one such example.

Maltese history is interwoven with the Mediterranean’s, however, as Mallia-Milanes notes, ‘traditional historians have tended to approach the island in almost complete isolation, which doesn’t make sense at all. No event or series of events at any point in time can make complete sense outside its wider context if it is weaned off its broader framework.’ To understand the Great Siege, he explains, we need to look at the bigger picture.

Malta and the Knights 1565

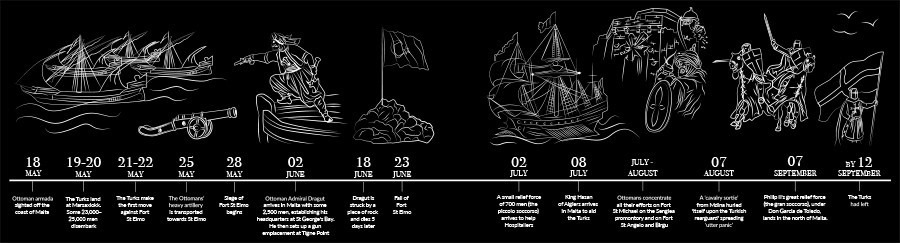

In 1565, the Ottomans besieged Malta for four bloody months, laying waste the island which the Knights Hospitaller of the Order of St John called their home. Atrocities abounded, one worse than the other. But what led to this confrontation? The seeds were sown in 1113, when Pope Paschal II took the order under his wing, finally formally recognising it as a privileged order of the Church. Based in Rhodes, the order made itself a thorn in the Ottoman Empire’s side, attacking Turkish trade ships doing business in the Levant and making a mockery of them. The Ottomans reacted, attacking Rhodes twice, proving successful in taking the island on their second attempt in 1522. Not long after, Sicily’s King Charles V gave the Maltese Islands and the port of Tripoli to the order. 1551 rolled around, Tripoli was taken by the Ottomans, and the order made a gruesome stand. It proceeded with fury to prove its indispensability as widely and convincingly as possible, looting Muslim villages, disrupting Muslim trade and commerce, and dragging Muslim men, women, and children into slavery. In doing so, the order thwarted the Ottoman Empire’s expansion westward.

During the 1560s, Malta still formed part of the late medieval Mediterranean world. With a native population numbering between 25,000 and 30,000, the island was rural and its economy predominantly agrarian. The capital city, Mdina, was weakly fortified. The small fort St Angelo, equally poor in its fortifications, guarded the entrance to the island’s deep and spacious harbour, with Birgu as its suburb. The forts lulled the native population into a false sense of security, but this was rectified after the loss of Tripoli, with the construction of two new forts: St Elmo and St Michael.

Hospitaller activity made Malta a target. The Ottoman Sultan Süleyman I sought to besiege Malta and bring the knightsʼ headquarters down. ‘The only way to bring such hospitaller hostility to an end was to try and eliminate the institution that sustained it once and for all. That, and only that, explains 1565. Francisco Balbi di Correggio’s [who served in the Spanish contingent during the siege] claim that the sultan wanted Malta to garner a stepping stone to invade Sicily and make larger-scale enterprises more feasible does not sound very convincing,’ reveals Mallia-Milanes.

On 18 May 1565, the Ottoman armada with some 25,000 men made their terrifying appearance in Maltese waters. Under the leadership of the Grand Master Jean de la Valette, 500 hospitallers, and around 8,000 Maltese men rallied, grossly outnumbered by the Ottomans. Battles and bloodshed pushed the island and its people to the brink that summer, but by the second week of September, the invincible Ottoman armada was sailing back home, embarrassed and humiliated. It was Spain’s gran soccorso (great relief), consisting of an 8,000-strong army, that saved the day. But the price to be paid for that victory was steep. The island lay in ruins. The countryside was ravaged and devastated. The victorious Grand Master de la Valette rose above it all, focusing on his victory and celebrating it with the construction of a new fortified city that would bear his name—Valletta.

Innovations in history

The enlightened French philosopher Voltaire once wrote; ‘Rien n’est plus connu que le siège de Malte.’ (Nothing is better known than the Siege of Malta). But plenty of questions remain.

Mallia-Milanes dissects its very name. What makes the ‘Great Siege’ great? This is the innovation in history he speaks of—the qualifying term which denotes the essence of the siege; ‘It does not consist of any discovery of new documentary facts. It is a re-evaluation, a rethink,’ he asserts. The question regarding what makes the siege ‘great’ seeks to determine the criteria that could be adopted to measure greatness. Since a continuous process of change constitutes the quintessence of history, the criterion the professor adopts here is to assess the phenomenon’s capacity to bring about any long-term structural change of direction. In this sense, how historically significant was the siege? The answer proves quite controversial. The episode and its outcome did not bring about major changes. As Mallia Milanes states, ‘In the long-term historical development of the early modern Mediterranean, no radical, no permanent changes may be convincingly attributed to the Ottoman siege of Malta.’

“The only way to bring such hospitaller hostility to an end was to try and eliminate the institution that sustained it once and for all. That, and only that, explains 1565.”

Another controversial issue concerns the timing of the siege: why did the Ottomans decide to besiege hospitaller Malta in 1565 and not two or three years earlier? In 1560 most of the Spanish armada had been destroyed at Djerba (present Tunisia). In 1561 the Ottoman Admiral Dragut destroyed seven more Spanish galleys. In 1562 a storm wrecked the armada’s remaining 25 galleys off the coast of Malaga on the western shore of the Mediterranean. By then, Spain was in no position to offer any naval assistance to the hospitallers. ‘The Ottomans could not have been unaware of these dramatic events,’ notes Mallia-Milanes. That would have been the ideal moment to strike, but the Ottomans failed to do so until a new Habsburg armada had been constructed, equipped, and fully armed. Mallia-Milanes continues: ‘This failure on the part of the Ottomans, whatever the reason, may explain the outcome of their hostile expedition to Malta.’

Mallia-Milanes also points out that barely anything is known about ‘the part played by most of the members of the local clergy and the Maltese nobility during the siege.’ What did they do? What was their role in this huge war?

Malta after the siege

‘The humiliating departure of the besiegers in September 1565 confirmed the orderʼs permanent sojourn [on Malta],’ notes Mallia-Milanes. For Malta and the Maltese, the order’s long stay on the island ‘constituted a revolutionary force in its own right, whose ingredients included long-standing hospitaller traditions, practices, a highly elitist lifestyle, courtly manners, ambitions, aspirations, values, their social assumptions, and social patterns, their widespread network of prioral communications, and especially their revenue, flowing regularly from their massive land ownership in Europe into the Common Treasury to be invested in Malta to finance their activities and to render the infrastructure more efficient,’ Mallia-Milanes comments. These elements drastically transformed Maltaʼs social and economic reality, triggering the island to move from late medieval into early modern times.

The knights invested lavishly in Malta, fortified it, urbanised it, and Europeanised it. The population grew steadily from some 12,000 to well over 80,000 between 1530 and 1789, during the time the order ruled Malta. Cotton and cumin industries flourished, as did the island’s slave market. The inhabitants enjoyed efficient medical and social services, advanced by the standards of the time. ‘[…] Malta of 1530 or 1565 and Malta of 1800 were two widely distinct islands. The knights placed the island firmly on the geopolitical map,’ asserts Mallia-Milanes. For hospitaller Malta, the long-term impact of the siege was ‘great’, highly significant and important. And the same may be said of the Order of St John.

And while the rule of the Knights in Malta ended some 226 years ago, this was by no means the end of the history of the order. ‘The history of the Order of the Hospital spans more than 900 years and still shows no signs, no symptoms, of waning,’ Mallia-Milanes explicates. The resilience of the institution, its capacity to recover quickly from any crisis, is what makes it so enthralling.

The beauty of historical research lies in the fact that nobody can claim the last word. There are no time machines to bring the theories and musing to an undeniable conclusion. And that is not necessarily a bad thing. As Mallia-Milanes notes: ‘It is always healthy to revise and update our knowledge of the past; it is necessary and vital to rethink it. It is in this sense that the past is always present, always alive.’

Comments are closed for this article!