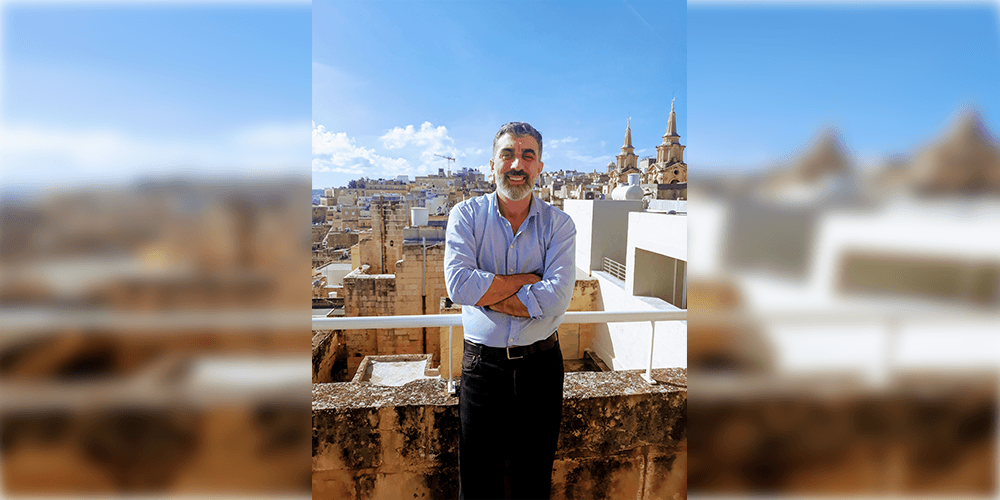

A new European Commission tool facilitates easy and accurate translation between English and Maltese. Author and translator Mark Vella is tirelessly promoting this translation product. He speaks to Teodor Reljic about how the Maltese language and its literary heritage has defined his life and career from graduation onwards.

The Maltese language is a defining element of Mark Vella’s life and career. First, he served as a sixth form Maltese teacher at the St Aloysius College, and set up a Maltese publishing house. He later on moved to Luxembourg as a Maltese translator in the mid-noughties and became a published author.

Now serving as Language Officer at the Directorate-General for Translation (Maltese Language Department) within the European Commission Representation in Malta, Vella recalls the mixed cocktail of emotions and expectations that greeted him when he first started reading for a Maltese undergraduate degree at the University of Malta back in 1994. ‘Unfortunately back then Maltese was still considered to be something of a “Cinderella course”,’ Vella tells me as we chat in his Valletta office. ‘The English Department was always [seen as] the more “sophisticated” option and sadly, Maltese was always considered to be the domain of the “losers”,’ he says with a wry smile. The course was then quite small in every respect, with just 10 students.

Eventually the zeitgeist started changing. ‘The next generation of lecturers who came up – like Bernard Micallef and Adrian Grima – began to apply a more modern approach to the course, and so revitalised it [to become] more outward-looking [and] forward-thinking.’ But Vella did not get to enjoy this scene, even if his experience of academia did nudge him towards some future research paths. ‘It was after I went through my Master’s course in Maltese that I developed a fascination with the Maltese short story, and the work of Juann Mamo in particular…’ In 2010, his interest in Mamo led to him editing a publication of Mamo’s short works, called Ġrajja Maltija, for Klabb Kotba Maltin.

But the pleasures of such intellectual pursuits would come later for Vella. Upon graduation, he decided to pursue his Postgraduate Certificate in Education, which left him quite ‘appalled’. ‘I found that the default, inherited approaches we have towards teaching the Maltese language do tend towards the stifling,’ Vella says. ‘We get bogged down in grammar, have an unhealthy obsession with “Malti pur” [pure Maltese], and generally just prevent kids from expressing themselves naturally.’

Vella remembers how English literature novels and textbooks were written in a far more engaging way than their Maltese counterparts. ‘Now, to be fair, I wasn’t teaching during the Denfil days,’ Vella says, referring to the previously standard, and intellectually bereft, Maltese-language reader. ‘But I did often find myself in a situation where I had no choice but to “invent” my own resources ad hoc.’

Despite all these frustrations, the needs Vella saw in his students were the same as his. ‘I noticed them responding to the lack of variety and choices available, so that pushed me to take a more pro-active and creative approach towards introducing them to the language, and to Maltese literature in particular,’ Vella remembers. ‘When you’re teaching young adults, there’s a thrill to noticing what tickles their fancy, and realising that you can in fact make Maltese literature relevant to their experience.’

Vella’s sensitivity to the pulse of Maltese literature led him to set up the boutique publisher, Minima. Although comparatively short-lived, the enterprise started a literary revolution whose after-shocks are still being felt. ‘The idea started brewing in my mind during my final year at university. I began to observe certain trends in Maltese writing, and thought that a new anthology of short fiction and poetry would be the way to go.’

This all happened before social media, so how did Vella go about scouting for works? ‘Yes, it was more challenging back then for obvious reasons. I’d like to refer to them as the kittieba tal-kexxun [‘desk-drawer authors’] who wouldn’t always showcase their works openly, and there weren’t all that many avenues for all that to begin with.’

Nevertheless, Minima can go down in history for being the first publisher to take on Immanuel Mifsud, now a leading figure of Maltese literature, and whose work Vella first encountered through self-published early volumes. Another notable discovery was author Ġużè Stagno, whose grittily humorous works were self-consciously touted by critics and commentators to be the expressions of a new literary ‘enfant terrible’ on the Maltese scene. Minima released Stagno’s debut novels, Inbid ta’ Kuljum (which grew from a TV series brainstorming session) and Xemx, Wisq Sabiħa, whose multi-protagonist tale of local debauchery promised the arrival of a ‘Maltese Irvine Welsh’. Like Mifsud, Stagno would go on to publish later works in mainstream venues after Minima folded, cementing that publisher’s un-ignorable impact in grooming literary talent.

Stagno’s latest work, ‘What Happens in Brussels Stays in Brussels’, intersects with Vella’s life post-teaching, and post-Minima. Though the narrative of the novel (published by Merlin in 2013) is very much its own thing, its context runs in parallel to Vella’s career trajectory: heading off to Luxembourg to work as a Maltese-language translator, forming part of that first wave of translators that emerged in a post-EU accession Malta.

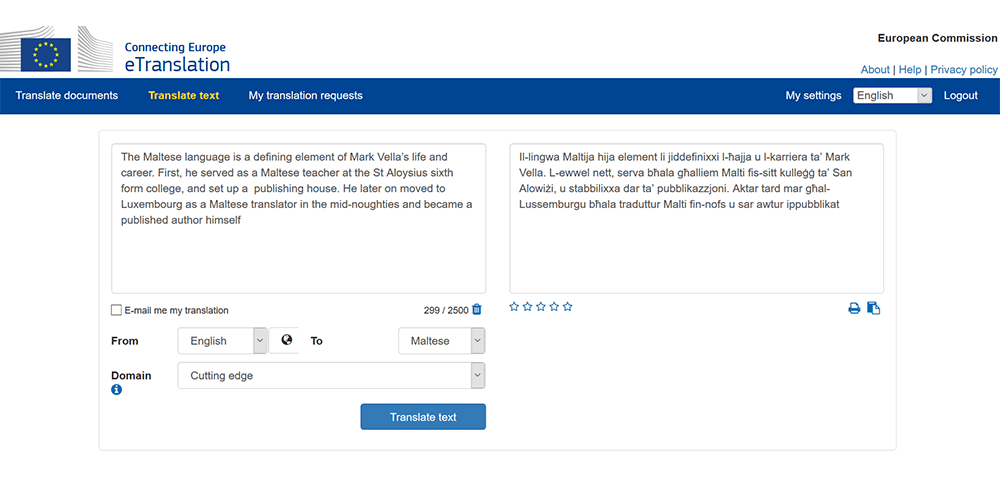

When we meet, he’s thrilled to talk about the Commission’s eTranslation tool – an efficient and easy-to-use product meant to facilitate translation of documents and available, for free, to all public service officials and academics in the EU, Norway, and Iceland until 2020.

‘Malta has an added advantage when it comes to this tool as we’re very much a bilingual country, unlike others who would need a bridge translation to English [using English as an intermediary language between two others — ed.] before making use of the product,’ Vella says, while talking about an undeniable dichotomy between speech and writing. ‘Maltese is widely spoken amongst families, groups of friends, other social, and even professional contexts. The problems seem to start at the written-word level. You can still see a cultural resistance to Maltese, even when it comes to administrative or bureaucratic procedures,’ he elaborates.

He soon brings up an example. ‘Say you want to apply for a loan from the bank. You’ll book an appointment with the bank official, and your face-to-face conversation with them will likely be in Maltese. But any follow-up paperwork and correspondence that you’ll receive will be written in English.’

According to Vella, the eTranslation product helps to address this confidence gap. ‘We’ve met with public officials and shown them how the product works, and they were thrilled to see it in action — the possibility of translating documents into Maltese quickly, while being safe in the knowledge that the translation was fully “legit”, came as a great relief. A lot of these departments are handling a large volume of translation regularly, and so a product like this is crucial.’

And if you’re thinking, why develop new solutions when we have Google Translate, Vella assures me that the eTranslation platform has a distinct advantage. The eTranslation platform ‘doesn’t draw from any random subset of information — so that it will soak in linguistic cues even from social media posts and so on — but it bases itself on established sources. Another important advantage is that it is built on a neural, not statistical, machine translation model.’

Another happy offshoot of this product, according to Vella, is its potential to burst the ‘Brussels bubble’ of Maltese competency. The tool allows the same rigour and precision honed by jobbing EU translators — ‘Brussels Maltese’ — to trickle down into public service use.

With a wealth of experience behind him, Vella is back in Malta to work at the European Commission Representation in Malta, and he is happy to observe a further boost to the Maltese language. ‘Suddenly, the “Cinderella course” gave way to an exciting opportunity,’ Vella beams, an opportunity he is now living.

eTranslation is available to University of Malta’s academics and selected students (10 accounts per lecturer on a temporary basis) thanks to the European Masters in Translation quality label. Lecturers can apply for a personal account. More information here.

Article sponsored by the European Commission for Representation in Malta.