Whatever you inherit comes from your biological family. Unfortunately, this includes disease. Talking about inherited conditions can make people anxious, making them unwilling to discuss the issue with their relatives. After speaking to a number of people my impression is that it seems taboo to discuss these things. People seem to feel that they will be stigmatised or treated differently because of a genetic condition.

A fear of social stigma hinders beneficial research. Research needs the collaboration of patients, since by investigating their condition researchers can in the long run develop a treatment or therapy. Not only that, but avoiding certain discussions means that relatives who might be at risk of developing the same problem would not be aware of it. If a condition is detected too late there might be very little that can be done.

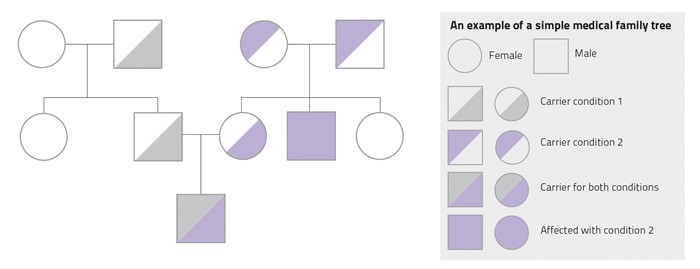

It is very useful to discuss these matters with your family and speak to your doctor together. By building a medical family tree you can easily see who might inherit what. This way, your relatives will learn more about their health and then seek treatment. For example, a cousin might learn that she has an increased risk of breast cancer and would therefore attend screening sessions to catch the cancer before it spreads. Not knowing that something is there does not make it go away but discussing medical matters with your family could save a relative’s life.

“It is very useful to discuss these matters with your family and speak to your doctor together”

Scientific studies need family medical information. Scientific studies using family trees have already shown how useful this information is in identifying families with a high risk for inheritable cancers, like colon and breast cancer. Other research showed that families can benefit from preventative treatments against cardiovascular diseases like diabetes.

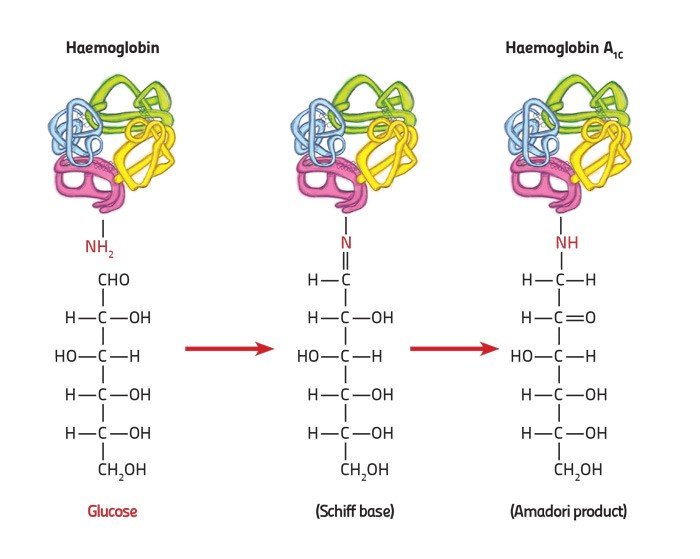

Local research has recently used this technique to find new genes, knowledge that can be developed for new treatments. The researchers were studying the genetic background of the protein which carries oxygen in our blood, haemoglobin. This protein switches from foetal haemoglobin to adult haemoglobin 3–6 months after birth. People with thalassemia have a problem with the adult version. Therefore, by studying local families that naturally cope well with the disease, they discovered the KLF1 gene that compensates for the malfunctioning adult protein by raising foetal haemoglobin levels. This was only possible with the help of family trees.

Speaking to a doctor to prepare a medical family tree (pictured) is done in the strictest confidentiality. You may also create your family medical history on https://familyhistory.hhs.gov/fhh-web/home.action to discuss with your family and doctor. I believe that it is in our best interest, apart from being potentially beneficial to the rest of humankind, to help in the creation of our own family medical trees.

If you have any queries when your physician or consultant asks you to prepare a family tree feel free to discuss them rather than avoiding family trees.