Learning Diversity: A Case Study of Refugee Students in Primary School is an international project created to provide information about the unique needs of refugee students, their obstacles to success, and the interventions and good practices applied to help them. Jonathan Firbank speaks with lead coordinator, Prof. Simone Galea, about the study’s ethics, methods, and findings.

Continue readingHands-on Activities to Bridge Skills Gap between Education and the Labour Market

Public dialogue in developed countries is ramping up about transforming education systems to help students better prepare for their post-academic life. Yet the global business landscape faces severe talent shortages, fuelled by a particular lack of skills – not degrees or certificates.

Continue readingWhat COVID-19 has taught us about education

While sitting in my living room and staring at a computer screen split into 4 squares (each with its own head), I talked with Dr Charmaine Bonello, Dr Tania Muscat and Dr Josephine Deguara from the Department of Early Childhood and Primary Education (DECPE), at the University of Malta (UM). I was curious about the changes in the education system during the pandemic. While the pandemic has allowed some of us to work from home, the education sector has faced certain challenges. I talked with the three researchers about how the pandemic has affected the education system, with a focus on five particular stakeholders in Early and Primary Education.

Continue readingQuality Education for All

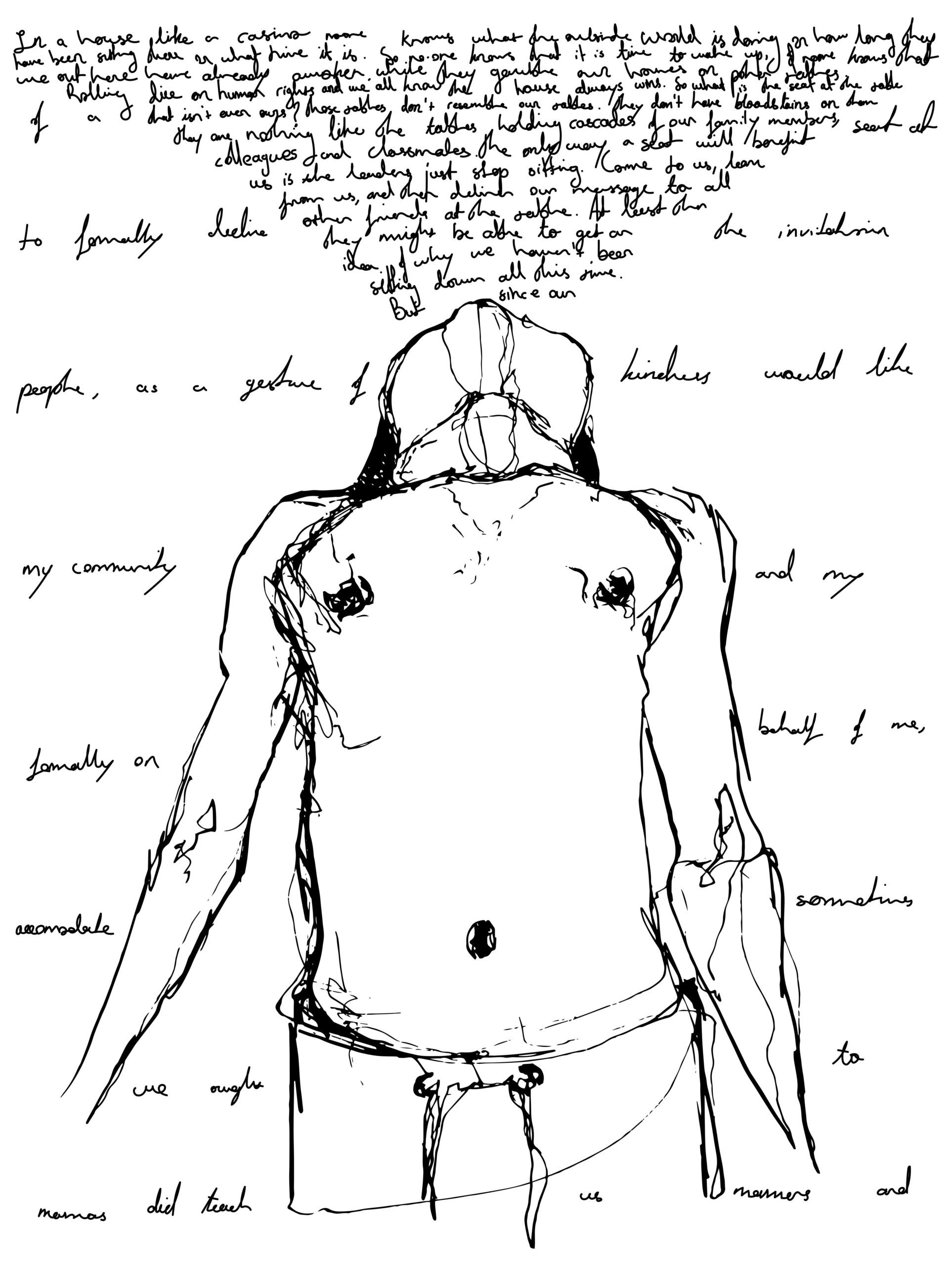

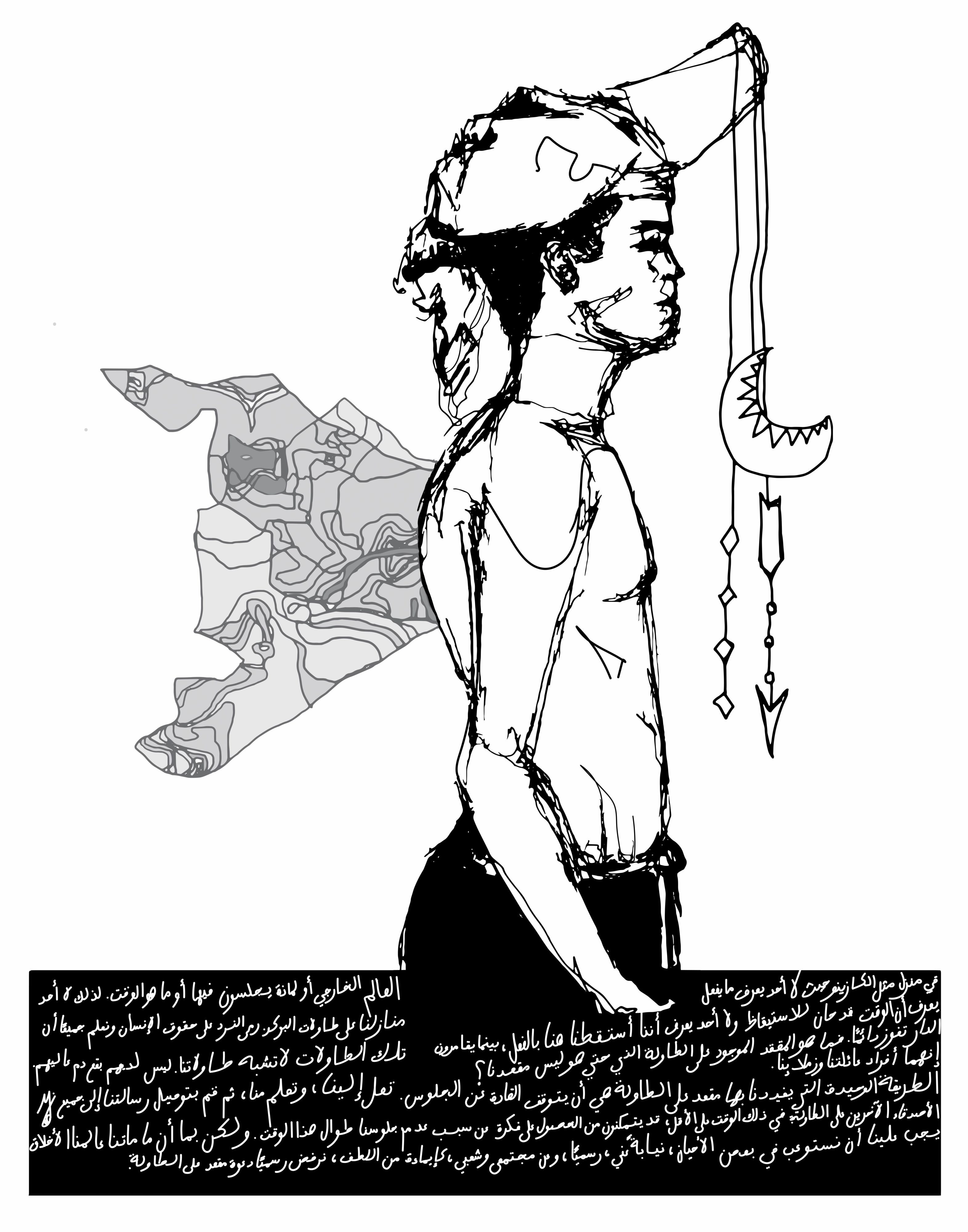

In today’s society, more than 262 million children and youth are not in school. To combat this, the United Nation established Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) in order ‘to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all’ by 2030. One of these goals, SDG4, is on the importance of quality education, which inspired two art pieces created by Zarifa Dag and Martina Camilleri.

Both artists took part in a design competition organised by the University of Malta’s Faculty of Education, asking participants to submit creative designs inspired by the theme of SDG4, which focuses on inclusive and equitable quality education.

Zarifa has a background in graphic design and digital arts, and her submissions for the competition were heavily inspired by her dual cultural identity, as she has both European and Middle Eastern roots. She travelled to Lebanon in 2018 and volunteered in refugee camps, working with the children of immigrants who fled to Lebanon because of conflicts happening in countries like Syria. This experience allowed her to witness first hand the differences in quality of life and education between children in Malta and refugees.

Zarifa’s piece is titled Halep’te, which is Turkish for “In Aleppo”, referencing one of the major cities in Syria. Her illustrations centre around an adolescent, representing the younger generation and their future, as well as the people that are at the centre of SDG4. She brings in multiple cultural references through the turban (the Middle and Far East) and crescent (Islam). While her narrative begins with a somewhat bleak representation of the current situation in children’s education, it ends with an element of hope that the situation may improve.

Martina Camilleri, who is currently reading for a Masters of Art in Social Practice Art and Critical Education, presented her take on SDG4 and quality education through a piece titled En Root – a play on the term ‘en route’ – which explores the journey someone takes to get their education. For her first artwork, Seeds We Sow, she asked 40 participants about why they keep looking for education or teaching opportunities. She then photographed their hands and transferred the images onto wooden planks, writing their responses behind each individual plank.

Her second artwork, titled One Piece, consists of five distinct pieces made from ceramic and mixed media. They represent the five objectives outlined in the Universal Agenda towards quality education: People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership. The pieces do not embody any of the terms individually. Instead, the art views the terms as a unified whole.

Zarifa and Martina’s artworks can be viewed along the main staircase of the Faculty of Education in the Old Humanities Building at the University of Malta. Although the artists interpreted the SDG4 in different ways, they both emphasised the importance of human-centred design. In essence, if somebody is going to use the product, then they should help construct it. The same approach could help achieve quality education for all children, despite socio-economic factors.

Innovators play a different game

South Africa-based entrepreneur Rapelang Rabana says that when it comes to innovation, the skills and experiences we accumulate over our lifetime are better resources than formal qualifications. Words by Daiva Repeckaite.

Continue readingArt for the mind

How can we use art to address mental health stigma? Dr Alexei Sammut writes about the art book Living with Mental Illness and the accompanying exhibition, which are his contributions to strengthen the discourse on mental health in Malta.

Declining mental health is a global burden. Anxiety, depression, and substance abuse are on the increase. Current estimates from the World Health Organization report that one in every four of us will experience some form of mental health challenge during their lifetime. By 2020, these figures are expected to double. And while support services do exist, their accessibility can be difficult.

There is no one explanation for this. The issue is complex and multifaceted. A lack of information on such services is a major contributing factor, however, stigma continues to be the main reason people refrain from seeking support and advice. Just a decade ago, discussing depression, eating disorders, self-harm, and suicide in Maltese public fora was unimaginable. And while things have improved—social media provides plenty of evidence—we cannot become complacent.

As part of my PhD, I looked into the attitudes of Maltese nurses and midwives towards mental illness. As people working in caring professions within medical settings, they are on the front lines of community health, seeing people from all walks of life, day in day out.

What I found was that while local nurses and midwives hold a positive attitude towards individuals with a mental illness, continued education, public engagement, and mental health literacy promotion are imperative.

Nurses and midwives who followed specific mental health nursing training held the highest positive attitudinal scores. This finding highlights the important correlation between education and mental health literacy to the attitudes towards those with a mental health condition. Without adequate mental health literacy, stigmatising attitudes will prevail, and people will not receive the care they need.

With this knowledge in hand, I wanted to raise awareness around mental health. To do this, I combined my goal with my love for art, collaborating with local artist Anthony Calleja to explore the lived experiences of living with mental illness.

Calleja produced 18 works of art, all of them depicting mental illness based on first hand accounts from people living with the diseases. The idea was to increase awareness and generate discussion without the need for text. Visual art allows for nuanced personal interpretation, empowering the individual to reflect and absorb the messages within the art they are viewing. People use metaphors to relate to their life situations, especially when things become difficult to explain. Like metaphors, art can be used to express things that cannot be stated in words. Art can be a therapeutic medium that helps people reach out. But this was not all we planned to do with the initiative.

Calleja’s pieces were collocated into a book titled Living with Mental Illness. The publication was launched at an exhibition of the original works. On the night, I conducted a study through questionnaires investigating people’s own interpretations of the works and the emotions they conveyed.

Although data analysis is still at a preliminary stage, findings seem to agree with the national survey on health literacy carried out in 2014 by the Maltese National Statistics Office on behalf of the Office of the Commissioner of Mental Health. In 2014, research showed that 42.5% of the Maltese population have a problematic level of health literacy. This further highlights the importance of education and health promotion campaigns.

We’ve all heard someone around us say that mental health is as important as physical health, and we need to act on that adage. We cannot shy away from giving it the attention it deserves. Now is the time to speak out and collaborate as a collective. We need to listen closely to those among us who are struggling, especially to those who use our community’s mental health services. Only they can help us revamp and address the challenges that lie ahead.

#GetLearnD

Students tutoring students

According to MATSEC, two in every three 18-year-old students don’t make it from sixth form to university. Gail Sant speaks to the team behind LearnD to find out more about their take on student-centred education.

You love films, videos, and photos. You relax while watching Netflix, and learn new skills on platforms like Skillshare and YouTube. Me? I adore the written word. Books, magazines, blogs are all I need to live a happy life. People are unique. And we all learn things in a unique way.

Different people require different teaching methods to learn. But most classroom set-ups involve one teacher, one lesson, and thirty-odd students. The lesson is interpreted in thirty different ways; a few absorb more than others, leaving some in need of extra help to ace their maths test. And how do they do that? With private lessons.

In Malta, private lessons are the go-to solution for students struggling with a subject. However, these sessions tend to be a carbon copy of school classes: one tutor, one lesson, multiple students. This problem was the seed that gave rise to the education-focused startup LearnD.

The philosophy

LearnD is a tutoring app invented by Luke Collins, Jake Xuereb, and Dr Jean-Paul Ebejer (Centre for Molecular Medicine and Biobanking, University of Malta). The concept behind it is simple, Ebejer says; ‘it’s a bridge between students who can act as mentors and students who need the help.’

LearnD does away with the one-size-fits-all standard of teaching and offers students tailor-made tutoring. Individuals are treated as such, their problems tackled through dedicated sessions. As a student, you don’t need to sit through a whole syll

abus of private lessons. The idea is to identify your weak points and hone in on them in select sessions. This is both time and money-efficient.

Xuereb believes ‘private lessons can make students lazy.’ They don’t need to evaluate their problems, or focus on where their issues lie. Not when they know they’ll just cover all the topics at various points during their weekly appointment with their second teacher on Tuesday night. LearnD focuses on dividing attention unequally. If you get an easy A in physical chemistry but struggle to pass organic chemistry, it only makes sense to give the latter some extra TLC. To get to this point, students need to take a step back from their desks and separate their strengths from their weaknesses.

This is also a big plus for tutors who don’t want to (or can’t) commit to teaching a whole syllabus. They can simply prepare a lesson for the requested topic and leave it at that, earning some extra money to accompany their stipend while gaining teaching experience.

But LearnD isn’t just about academia. Some lecturers lose touch with ‘the student life’, distancing their relationship with students. Conversely, student-tutors know the struggles a peer would be going through and can provide support. ‘No one would have a better understanding of what a sixth former needs to do to get into medicine than a medicine student,’ says Xuereb. ‘Through LearnD you can find people who have been through the exact same thing and who can offer their best advice on anything from time management to de-stressing, and everything else.’

Making it happen

The original concept was more related to finding a way for academically inclined 6th form students to contribute productively to society,’ says Xuereb. When he spoke to Collins, a fellow University of Malta student and Xuereb’s former maths tutor, the idea went from ‘an online local network’ to ‘app’. At the time, there were no local tutoring apps.

Despite both being passionate about the idea, they soon realised that they needed someone with business experience, and that’s where Ebejer came in: the LearnD team was born!

The process that made this idea into reality was not a simple one. Xuereb and Collins spent over six months working on the app, learning about the tech behind app-making and coming up with a business plan.

They got their break when they won the Take-Off Seed Fund Award in 2018 and got the necessary funds to make the app a reality. They quickly got the ball rolling, hiring designers, app developers, and marketing agents. The team grew; the app was built. Then, during the KSU Freshers’ Week in 2018, the app was partially launched, inviting potential tutors to apply. The app is now fully launched and available for students.

Troubles

As with all big projects, the team ran into a few setbacks along the way. One prominent techy mishap didn’t allow them to launch the app on the Apple Store, making it difficult to keep up with the launch date.

Since the app is used by underage students, there were also a lot of safety features which needed inclusion. Tutors upload their police conducts and ID cards. Also, to make sure LearnD’s service is reliable, the team not only analyses tutors’ qualifications, but they also try and test each applicant out themselves. And for accounts which belong to students under the age of 16, parents need to authorise any communication which goes on through the app.

The team persisted through the struggles they encountered and continue to work hard to solve any problems which crop up. Despite difficulties with time management, Collins and Xuereb, both undergraduate students, expressed how this app allowed them to dive into the working world. They gained entrepreneurial maturity, understanding the importance of a reliable team which shares the same ideas and work ethic, as well as dividing funds for the project’s overall benefit.

A LearnD future

The LearnD story doesn’t stop here. ‘We want to renovate the education space,’ says Ebejer, adding that they wish to take the next step and make it internationally available. Malta’s size makes it the perfect test bed, but they think that the app shouldn’t be limited to its home.

According to MATSEC, in 2017 only 27% of 18-year-old students acquired the necessary qualifications to get into university. Collins expressed that students ‘shouldn’t get lost’ because of a bad exam result or because of a mismatched student-teacher scenario. Students deserve to be treated as individuals, and LearnD can offer them that.

Protecting prisoners from radicalisation

Curbing extremism and violence is high on the global agenda. With prisons known to be a breeding ground for recruiters, are we doing enough to protect our inmates? Michela Scalpello writes.

Continue readingConserving brushstrokes

A new conservation project will soon start work on one of Malta’s most significant historical artworks. Laura Bonnici meets Prof. JoAnn Cassar, Jennifer Porter, Dr Chiara Pasian, and Roberta De Angelis to find out why conserving the d’Aleccio Great Siege Wall Painting Cycle is of national importance.

Continue readingSustaining mobilisation: what will it take?

You can’t watch Blue Planet and not feel a pang of guilt for the plastic straw in your drink. But what does it truly take to mobilise people and encourage more sustainable behaviour? Kirsty Callan talks to Dr Vincent Caruana.

We’re finally living in a world where environmentalism is a sexy topic. Everywhere you look, it’s vegan-this, plastic-free-that. And it’s wonderful. Public awareness of the impact we are having on our planet is on the rise, and yet, according to Eurostat, Malta still registered the European Union’s highest increase in carbon dioxide emissions from energy use in 2017.Researcher Dr Vincent Caruana (Centre for Environmental Education and Research, University of Malta [UM]), believes the crises we are facing can be summed up in one double challenge: the eradication of poverty and the preservation of the environment. By simplifying the issue, it is turned into a single problem rather than many overwhelming issues, highlighting the interconnectedness of the challenges we face, be they social, economic, or environmental.

Taking Nepal and Bangladesh as examples, both have suffered devastating floods. Some point to large-scale deforestation by logging companies and agricultural businesses, as well as locals using the forests’ resources. Some environmentalists point to the population and blame them, saying that the increasing use of the forest by locals places burdens on the region’s resources, suggesting that their activities are the current major source of environmental problems. But that creates a scenario where the victims of poverty are blamed for trying to alleviate their own poverty. Meanwhile, the reality is that the wealthiest one-fifth of humanity consumes so much more than the rest of the world, leaving the rest hungry.

Who is most to blame for these problems? International institutions such as the United Nations, national governments, transnational corporations, or consumers?

In his classes, Caruana runs his students through a similar thought experiment. Who is most to blame for these problems? International institutions such as the United Nations, national governments, transnational corporations, or consumers? Some argue that it is greedy transnational corporations, out to make a quick buck while ignoring environmental impacts. Some retort, saying that corporations are bound by economy to maximise profits. Others would point their fingers at the consumers who choose to buy from dirty companies instead of the most ethically sourced. ‘Of course, there is no correct answer,’ Caruana states. ‘There is no single solution. We need thousands of solutions working in parallel. Literally. The interconnectedness of it all requires both governments and civil society to commit time and effort.’

GETTING TO THE CRUX

Caruana’s doctoral research identifies the influences that lead people to engage in responsible sustainable behaviour and hones in on ways to sensitise and mobilise sustained civic action.

Caruana is quick to note that there are a plethora of barriers—social, economic, and political—which prevent people moving towards sustainability. What surprised him was that more personal barriers, such as frustration, hopelessness, and dealing with disappointments, also pose a problem. ‘This is a significant point, considering that environmental circles are oft en concerned with reaching out towards the unconverted rather than supporting the converted,’ he explains. In other words, we have to continue to motivate those who are already on the right path to ensure they don’t become demoralised.

Looking to understand how people can take control of processes that affect their lives, Caruana conducted four case studies. Among them were an intentional community in Malta and a Fair-Trade network in Egypt. ‘The power of case studies lies in their ability to reframe and critically challenge core beliefs that are now taken for granted, like how a municipality, church organisation, and a trade organisation ought to act,’ he says.

Caruana believes that education on sustainable development (ESD) lies at the heart of it all—and he is not alone. In 2015, representatives from 193 countries gathered in New York to sign off on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. At the opening ceremony of the summit, Ban Ki-moon referred to the the Agenda outlined as ‘a to-do list for people and planet’. One goal focuses on education, which includes the aim to ‘ensure all learners acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development by 2030.’

In Malta, ESD is established as a cross-curricular theme within the National Curriculum Framework. However, ‘in practice, it is still in the process of being concretely translated across schools and within subjects,’ Caruana notes. He also highlights the need for adults to be educated too, so that this cultural shift can truly happen; however, he is quick to follow up the notion with its own weakness. For years, adult ESD has remained ‘locked within ideologies which have caused many of our contemporary environmental problems.’ We need a complete overhaul of our outlook. Increased emphasis on recycling is a positive; however, what would be better is if we could reduce the amount of waste we are creating in the first place. This is but one example. ‘As long as ESD remains stuck within the same thinking that is creating the double challenge, there can be little progress,’ says Caruana.

CLEARING THE SLATE

Back in 2001, Caruana co-founded Malta’s Fair-Trade movement. ‘Faced with the continuous realisation of an unfair world trade system, and seeing first hand through my voluntary work how such a system creates poverty, my friends and I wanted to be proactive and part of a solution,’ he states. ‘The path forward was not chartered for us. We started off passionately, then with each step, we finally arrived to setting up a fair trade shop and an ongoing educational programme. Rather than complain, we have within us the power to create new solutions.’

This philosophy is at the core of what Caruana is doing now. ‘The current model needs to be challenged, and we do have the power within us to create new ways of thinking. We need a shift from thinking in terms of economic growth to growth in wellbeing,’ he says. Referring to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, Caruana says they had it right. ‘A country’s ability to develop more sustainably depends on the capacity of its people and institutions to understand complex environmental choices.’ We need real leaders, not token ones, who inspire, embrace and support citizens in their actions, and create new spaces for dialogue. ‘Both Civil Society Organisations and local institutions can be a positive force towards sustainable solutions at a local level.’

GETTING TOUGH

This mission is a beastly mountain. The reality is that there are major hurdles standing in the way of a paradigm shift that would see Malta’s people acting more sustainably. Beyond personal barriers, Caruana’s research reveals the vulnerability of local processes: ‘In Malta, a change in government results in a change in priorities (and support).’ Every five years, the system is shaken by an election that brings with it new agendas and philosophies. ‘Stability in environmental issues and processes is essential,’ he notes. Caruana also points out the fragility of civil societies’ human resources.

The solution, Caruana suggests, is ‘to create stronger links between governments, politicians, organisations, and citizens, both for research and to build a network of adult educators.’ This was highlighted in his Fair Trade case study where success was highly dependent on the level and consistency of engagement at both a local level with producers and with their partners in the west.

It is clear that good leadership is key. To help address this issue, he has created an Erasmus+ project called PEERMENT with the aim of coming up with a new model of mentoring and peer-mentoring for ESD. It involves about 20 education specialists as teacher trainers and senior mentors and about 50 teacher mentees.

‘We have to invest in leadership,’ says Caruana. ‘We need to focus on social learning and empowering institutions and organisations to work together and become innovative co-creators of new ways of thinking. In an ever-changing world, this is a challenge for educators to embrace with passion and urgency.’

Circling back to the double challenge, it is clear that no one project will be able to comprehensively solve the issues we are facing as a global society. But ‘we have to stop waiting for permission,’ says Caruana. ‘The beauty of the emerging paradigm lies in the reality that we don’t need permission to change outmoded mind-sets that no longer serve us.’ And this will be crucial in the road ahead.