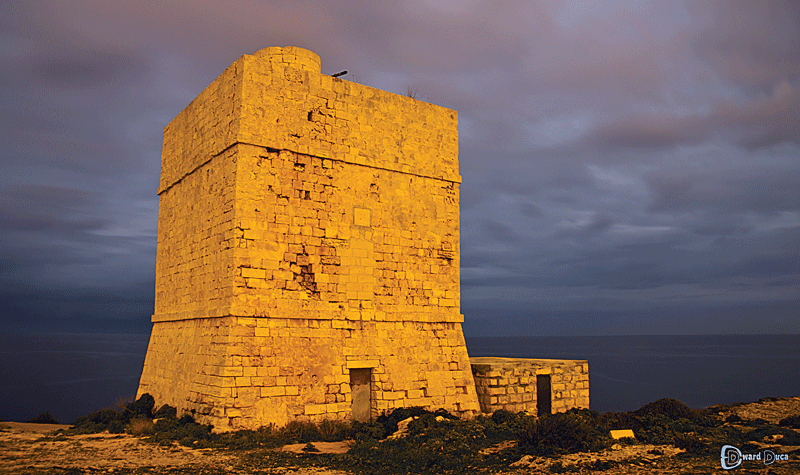

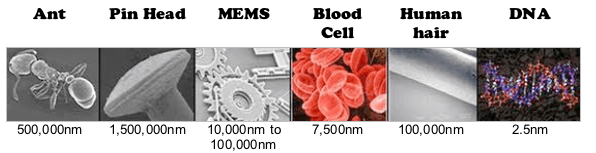

Roderick Micallef has a long family history within the construction industry. He coupled this passion with a fascination with science when reading for an undergraduate degree in Biology and Chemistry (University of Malta). To satisfy both loves, he studied the chemical makeup and physical characteristics of Malta’s Globigerina Limestone.

Micallef (supervised by Dr Daniel Vella and Prof. Alfred Vella) evaluated how fire or heat chemically change limestone. Stone heated between 150˚C and 450˚C developed a red colour. Yellow coloured iron (III) minerals such as goethite (FeOOH) had been dehydrated to red coloured hematite (Fe2O3). If the stone was heated above 450˚C it calcified leading to a white colour. This colour change can help a forensic fire investigator quickly figure out the temperature a stone was exposed to in a fire — an essential clue on the fire’s nature.

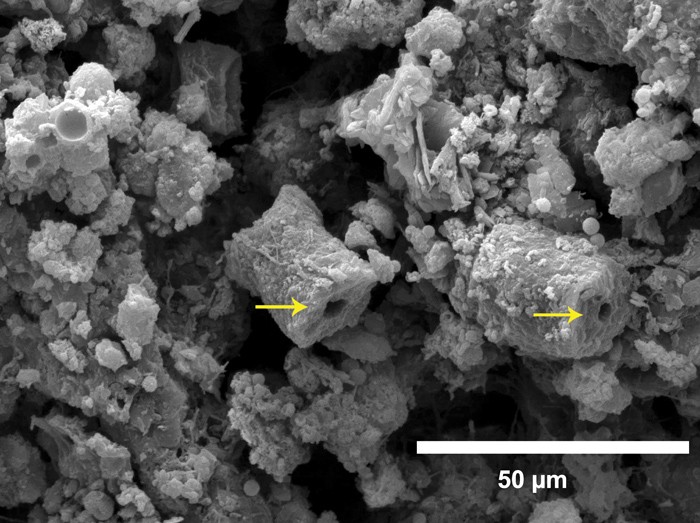

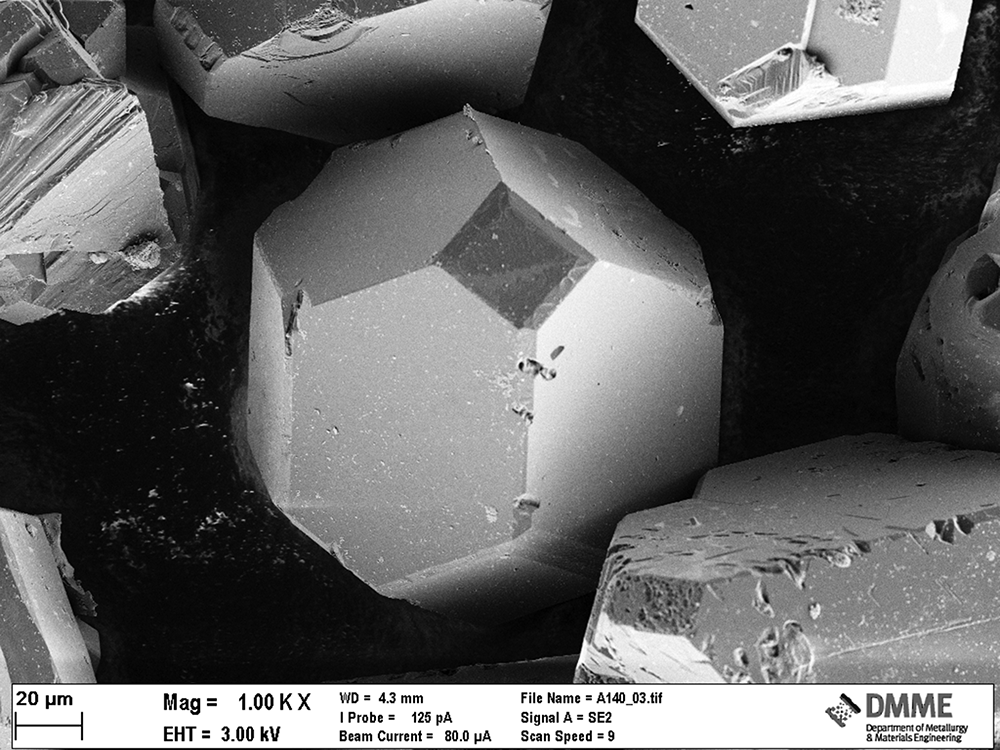

While conducting this research, Micallef came across an Italian study that had concluded that different strains of heterotrophic bacteria can consolidate concrete and stone. Locally, Dr Gabrielle Zammit had shown that this process was happening on ancient limestone surfaces (Zammit et al., 2011). These bacteria have the potential to act as bio-consolidants and Micallef wanted to study if they could be used to reinforce the natural properties of local limestone and protect against weathering.

Such a study is crucial in a day and age where the impact of man on our natural environment is becoming central to scientific research. The routine application of conventional chemical consolidants to stone poses an environmental threat through the release of both soluble salt by-products and peeled shallow hard crusts caused by incomplete binding of stone particles. Natural bio-consolidation could prove to be an efficient solution for local application and is especially important since Globigerina Limestone is our only natural resource.

This research is part of an Master of Science in Cross-Disciplinary Science at the Faculty of Science of the University of Malta, supervised by microbiologist Dr Gabrielle Zammit, and chemists Dr Daniel Vella and Prof. Emmanuel Sinagra. The research project is funded by the Master it! Scholarship scheme, which is part-funded by the EU’s European Social Fund under Operational Programme II — Cohesion Policy 2007–2013.

By Josef Borg

By Josef Borg

By Josef Borg

By Josef Borg