Maintenance is not the sexiest aspect of business, but diligent corrosion monitoring in the oil, gas, and maritime industry could prevent massive environmental accidents. Inês Pimparel writes on behalf of AquaBioTech Group.

The maritime industry is going through massive developments. Traditional oil and gas remain powerful, as does the shipping industry, but there is a big rise in more sustainable businesses such as offshore wind and solar energy farms. Corrosion affects them all equally.

The NACE International Institute estimates that corrosion costs the maritime industry between $50 and $80 billion every year. Clearly, maintenance is an expensive practice, which might lead to neglect, resulting in catastrophic environmental incidents.

A low-cost, eco-friendly, and efficient solution is needed to monitor corrosion and enable earlier repair.

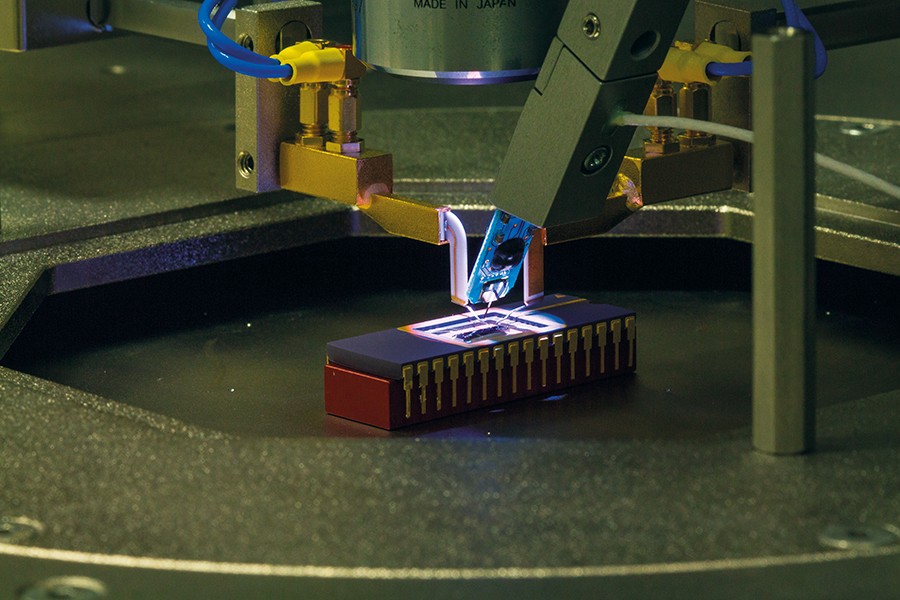

The industry currently monitors structures using ultrasonic or magnetic sensors. However, other solutions exist. The University of Aveiro (Portugal), the Norwegian research institute SINTEF, and the Maltese company AquaBioTech Group are working on SMARTAQUA, an innovative but simple approach that uses a special paint.

It uses environmentally-friendly nanomaterials to form a functional solid film over surfaces such as the support for a floating fish farm or the base of a wind turbine. Because the nanolayer goes directly onto the structure, it can combine colorimetric with magnetic analysis to detect corrosion as it happens.

The detection method will be tailor-made to the depth at which the metallic structure is placed to assess the integrity of the structures. Colorimetric detection is a relatively simple, user friendly, and reliable manner of detecting corrosion in splash zones. But in submerged structures, where colorimetric detection is not possible, the use of magnetic measurements would reveal the state of coated substrates.

The approach is not completely novel. The aeronautical sector is already introducing it. The AquaBioTech Group is performing toxicity tests on the nanomaterials using marine organisms such as microalgae and mussels. After this, the team will test the nanolayer’s efficacy on metallic structures in their offshore testing site close to St Paul’s Islands.

If this technology is proven safe and effective it will revolutionise the field of monitoring activities. It will reduce transport needs when assembling new offshore structures, indirectly reducing fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions. The commercial and environmental benefits are massive.

The project is highly collaborative. It brings together a small business, a research institute, and a university; testament that success can be achieved through co-creation, inclusivity, and sustainability—and that small advances can lead to a sea of change.

Note: This project was funded by the Research Council of Norway (through the programme of Petromaks II, project 284002), the Foundation of Science and Technology in Portugal, and the Malta Council for Science and Technology via the MarTERA – ERA-NET Co-fund scheme of H2020 of the European Commission.

H

H