Blood Families

Jeanesse Scerri discusses a inherited condition and what it does to us.

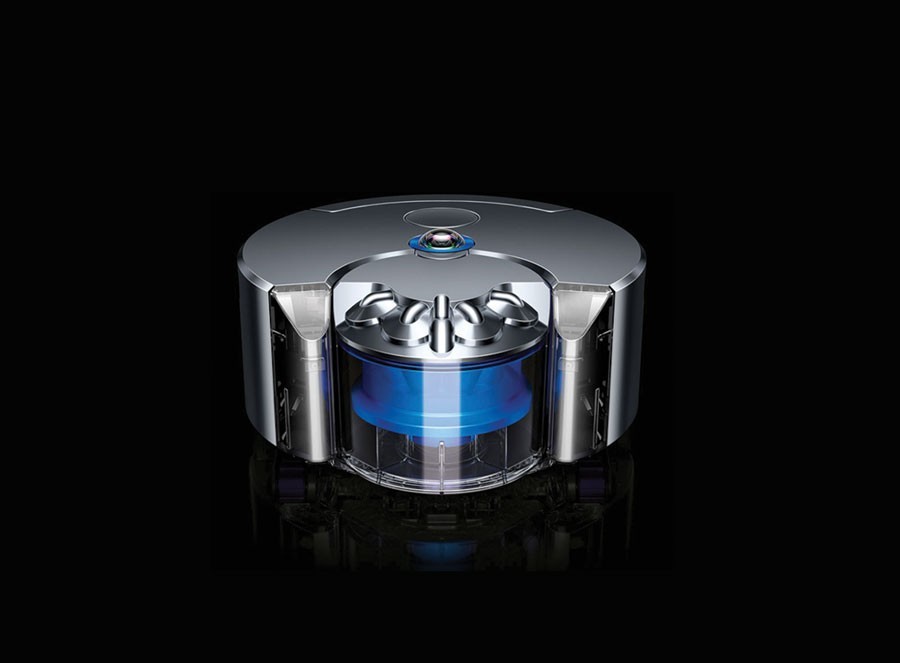

Robots: science fiction to science fact

Dr Ing. Raphael Grech writes about his love affair with the robot world from Wall-E to the MIT Lincoln Laboratory in the USA

Light up my Universe

What is the universe made of? How was it formed? How old is it? Will things stay the same forever?

The night sky is shedding its secrets as Ian Fenech Conti (Institute of Space Science and Astronomy) talks about his work measuring the most elusive matter in the universe.Continue reading

Hips 4 Eternity

All over the world, hip replacement surgeries are on the increase. Provisional data from the hip replacement register at Mater Dei shows that, in Malta during 2014, 145 people needed their hips replaced while another 11 needed revisions to old implants. With costs that run into the thousands, the problem of faulty implants caught the eye of a local research team of engineers and medics. Cassi Camilleri finds out more about their work in solving the dilemma. Photography by Elisa von Brockdorff

I_compute I_create I_am

Creativity is a quality that we, as humans, think is ours alone. Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis is creating computers that might have already taken this away from us. Computational creativity is here. His games are helping children be more creative, others to overcome dyslexia, and even combat bullying. Words by Dr Edward Duca.

Creativity is a quality that we, as humans, think is ours alone. Prof. Georgios N. Yannakakis is creating computers that might have already taken this away from us. Computational creativity is here. His games are helping children be more creative, others to overcome dyslexia, and even combat bullying. Words by Dr Edward Duca.

Gymnastic Polymers

by Alexander Hili

Forgetting what you can’t remember

How does the loss of memory change a person? Can media replace memory? Giulia Bugeja asks several researchers to find out the affect on cultural memory and she also touches on dementia

When Mike* went to the nursing home that evening to visit his grandmother Maria*, she was worried that he wouldn’t be able to find her because the caretakers had changed her room. Mike tried explaining to her that her room on the 4th floor had been refurbished a year ago, but she couldn’t remember.

‘Can life without memory be considered a meaningful existence?’ asks Dr Charles Scerri (Malta Dementia Society, and Department of Pathology, University of Malta). Dr Scerri researches dementia. He is currently examining which physical environments and what sort of psychosocial wellbeing can improve life in local dementia hospital wards. In fact, Dr Scerri reports that today there are over 44 million people suffering from some form of dementia. That is around 100 times the Maltese population. He asks, ‘what type of society can we end up with if we are wholly made up of individuals with no past and an uncertain future?’

With more people relying on new media technology to record information and experiences, Dr Scerri’s question faces a future society where media could replace memory. ‘It would be short-sighted to think that new media will have no long-term influence on the complex nexus of personal and cultural memory’, says Dr James Corby (Department of English, UoM).

Photography already acts as a surrogate for memory. But, it does not stop there; theorist Roland Barthes goes one step further saying how photography can capture details missed by the human eye. As developers of new media strive to enhance experiences, more users are adopting them. In the final quarter of 2012 alone, Apple sold 37.4 million iPhones. This smartphone, equipped with HD video, an in-built camera, calendar, and interactive 3D map helps people capture memories and avoid having to remember appointments or directions. It even comes with Siri, your own ‘personal assistant’, to use Apple’s words.

Despite these abilities, Dr Corby is sceptical. As a researcher working on the interfaces between literature, philosophy and culture, Dr Corby thinks that the rich tradition of the humanities should inform debates about cultural memory. ‘The idea that a facility to record memories leads to the diminishment of personal memory is by no means a new idea. Indeed, it is precisely the accusation that, in Plato’s Phaedrus, Socrates makes against writing.’ Writing did not steal our ability to remember and neither should new technologies.

“You can never really know if what she’s saying is true because her memories are not always real”

So what would happen if old or new media failed us? When the accounts office of the family business burned down, Mike could relate to his grandmother’s anxiety due to her lack of personal memory. All the accounting records, invoices, transaction records, and overseas payments were destroyed. The accountant was so shocked that he still will not enter his old office after 15 years.

The accountant had to keep paper records. There was too much information to remember and they couldn’t memorise it all. Although they recorded the information they still lost it in the fire.

| More about Alzheimer’s in Malta |

Dr Scerri has collaborated with the Department of Pathology to launch the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Group (University of Malta). Their objective is to gather several multidisciplinary professionals to ‘promote and facilitate research and scientific collaboration in Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia’. Together with Trevor Zahra, he recently released the publication X’ħin hu? Fatti dwar id-dimensja (What time is it? Facts about dementia). Dr Scerri has collaborated with the Department of Pathology to launch the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Group (University of Malta). Their objective is to gather several multidisciplinary professionals to ‘promote and facilitate research and scientific collaboration in Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia’. Together with Trevor Zahra, he recently released the publication X’ħin hu? Fatti dwar id-dimensja (What time is it? Facts about dementia). |

We all risk losing both valuable information and the recollection of experiences. So what would happen if Malta became a nation of people without a memory of important events? For Dr Corby, a society which relies on new media and less on memory ‘might then lead to a complete eliding of any difference between personal memory and an increasingly undifferentiated surfeit of readily available cultural memory — a sort of technologised and globalised cultural eidetic memory’.

There’s also the possibility that media such as photographs could lead to the creation of cultural memories which never took place. ‘I imagine false memory to be the norm—it would be naïve to think that the visual representation of a culture […] is free from ideology’ says Dr Corby. Our national identity will instead be formed around uncertain events.

Joe Rosenthal’s photograph of American soldiers raising the American flag on Mount Suribachi on the island of Iwo Jima signifies a moment of national pride for Americans. Few Americans are aware that the photograph shows the flag being raised for a second time. The first flag was too small but the second larger flag would be seen by incoming ships.

Similarly, on the 4th floor of a nursing home, an old woman recalls how the nurses refused to take down the Christmas decorations. In her room, there was only a lone poppy. ‘She often creates stories in her head’, says Mike. ‘You can never really know if what she’s saying is true because her memories are not always real.’

‘Memories are created by altering a set of connections between brain cells so that one cell stimulates the others,’ says Jonah Lehrer, Wired Magazine. By creating memories, we are literally rewiring our brains. Every time a memory is recalled, the connection between brain cells is restructured and the memory altered depending on the stimuli of the current situation. This means that whilst media may fail us, so might our memories.

Will a nation inevitably make the same mistakes because its people cannot remember past experiences or because they replace them with false ones? When asked how memory recall can be assisted, Dr Scerri acknowledges that media is a useful tool in improving memory, as ‘memory albums are extremely valuable for individuals with dementia in facilitating memory events and in reducing anxiety and confusion’. Perhaps these tools can help Mike’s grandmother.

*Names have been changed to protect the identity of the people mentioned in the article.

Giulia Bugeja is part of the Department of English Master of Arts programme.

Look out for an in-depth feature on dementia in the next issue.

Cybersexuality

Relationships have changed hand in hand with society. More couples are living far apart from each other. Marc Buhagiar speaks to Mary Ann Borg Cunen to explore how technology can lend a hand. Illustrations by Sonya Hallett.

An Intelligent Pill

Doctors regularly need to use endoscopes to take a peek inside patients and see what is wrong. Their current tools are pretty uncomfortable. Biomedical engineer Ing. Carl Azzopardi writes about a new technology that would involve just swallowing a capsule.

Michael* lay anxiously in his bed, looking up at his hospital room ceiling. ‘Any minute now’, he thought, as he nervously awaited his parents and doctor to return. Michael had been suffering from abdominal pain and cramps for quite some time. The doctors could not figure it out through simple examinations. He could not take it any more. His parents had taken him to a gut specialist, a gastroenterologist, who after asking a few questions, had simply suggested an ‘endoscopy’ to examine what is wrong. Being new to this, Michael had immediately gone home to look it up. The search results did not thrill him.

The word ‘endoscope’ derives from the Greek words ‘endo’, inside, and ‘scope’, to view. Simply put, looking inside our body using instruments called endoscopes. In 1804, Phillip Bozzini created the first such device. The Lichtleiter, or light conductor, used hollow tubes to reflect light from a candle (or sunlight) onto bodily openings — rudimentary.

Modern endoscopes are light years ahead. Constructed out of sleek, black polyurethane elastometers, they are made up of a flexible ‘tube’ with a camera at the tip. The tubes are flexible to let them wind through our internal piping, optical fibers shine light inside our bodies, and since the instrument is hollow it allows forceps or other instruments to work during the procedure. Two of the more common types of flexible endoscopes used nowadays are called gastroscopes and colonoscopes. These are used to examine your stomach and colon. As expected, they are inserted through your mouth or rectum.

Michael was not comforted by such advancements. He was not enticed by the idea of having a flexible tube passed through his mouth or colon. The door suddenly opened. Michael jerked his head towards the entrance to see his smiling parents enter. Accompanying them was his doctor holding a small capsule. As he handed it over to Michael, he explained what he was about to give him.

Enter capsule endoscopy. Invented in 2000 by an Israeli company, the procedure is simple. The patient just needs to swallow a small capsule. That is it. The patient can go home, the capsule does all the work automatically.

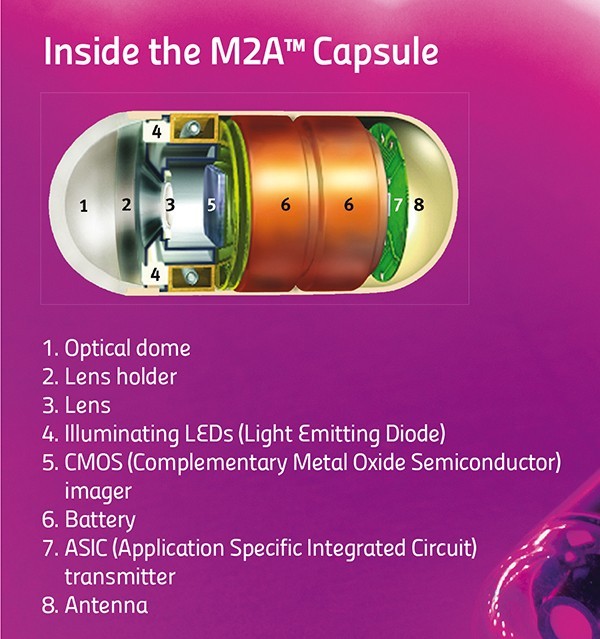

The capsule is equipped with a miniature camera, a battery, and some LEDs. It starts to travel through the patient’s gut. While on its journey it snaps around four to thirty-five images every second. Then it transmits these wirelessly to a receiver strapped around the patient’s waist. Eventually the patient passes out the capsule and on his or her next visit to the hospital, the doctor can download all the images saved on the receiver.

The capsule sounds like simplicity itself. No black tubes going down patients’ internal organs, no anxiety. Unfortunately, the capsule is not perfect.

“The patient just needs to swallow a small capsule. That is it. The patient can go home, the capsule does all the work automatically”

First of all, capsule endoscopy cannot replace flexible endoscopes. The doctors can only use the capsules to diagnose a patient. They can see the pictures and figure out what is wrong, but the capsule has no forceps that allow samples to be taken for analysis in a lab. Flexible endoscopes can also have cauterising probes passed through their hollow channels, which can use heat to burn off dangerous growths. The capsule has no such means. The above features make gastroscopies and colonoscopies the ‘gold standard’ for examining the gut. One glaring limitation remains: flexible endoscopes cannot reach the small intestine, which lies squarely in the middle between the stomach and colon. Capsule endoscopy can examine this part of the digestive tract.

First of all, capsule endoscopy cannot replace flexible endoscopes. The doctors can only use the capsules to diagnose a patient. They can see the pictures and figure out what is wrong, but the capsule has no forceps that allow samples to be taken for analysis in a lab. Flexible endoscopes can also have cauterising probes passed through their hollow channels, which can use heat to burn off dangerous growths. The capsule has no such means. The above features make gastroscopies and colonoscopies the ‘gold standard’ for examining the gut. One glaring limitation remains: flexible endoscopes cannot reach the small intestine, which lies squarely in the middle between the stomach and colon. Capsule endoscopy can examine this part of the digestive tract.

A second issue with capsules is that they cannot be driven around. Capsules have no motors. They tend to go along for the ride with your own bodily movements. The capsule could be pointing in the wrong direction and miss a cancerous growth. So, the next generation of capsules are equipped with two cameras. This minimises the problem but does not solve it completely.

The physical size of the pill makes these limitations hard to overcome. Engineers are finding it tricky to include mechanisms for sampling, treatment, or motion control. On the other hand, solutions to a third problem do exist. This difficulty relates to too much information. The capsule captures around 432,000 images over the 8 hours it snaps away. The doctor then needs to go through nearly all of these images to spot the problematic few. A daunting task that uses up a lot of time, increasing costs, and makes it easier to miss signs of disease.

A smart solution lies in looking at image content. Not all images are useful. A large majority are snapshots of the stomach uselessly churning away, or else of the colon, far down from the site of interest. Doctors usually use capsule endoscopy to check out the small intestine. Medical imaging techniques come in handy at this point to distinguish between the different organs. Over the last year, the Centre for Biomedical Cybernetics (University of Malta) has carried out collaborative research with Cardiff University and Saint James Hospital to develop software which gives doctors just what they need.

Following some discussions between these clinicians and engineers they quickly realised that images of the stomach and large intestine were mostly useless for capsule endoscopes.

Identifying the boundaries of the small intestines and extracting just these images would simplify and speed up screening. The doctor would just look at these images, discarding the rest.

Engineers Carl Azzopardi, Kenneth Camilleri, and Yulia Hicks developed a computer algorithm that could first and foremost tell the difference between digestive organs. An algorithm is a bit of code that performs a specific task, like calculating employees’ paychecks. In this case, the custom program developed uses image-processing techniques to examine certain features of each image, such as colour and texture, and then uses these to determine which organ the capsule is in.

Take colours for instance. The stomach has a largely pinkish hue, the small intestine leans towards yellowish tones, while the colon (unsurprisingly perhaps) changes into a murky green. Such differences can be used to classify the different organs. Additionally, to quickly sort through thousands of images, the images need to be compacted. A specific histogram is used to amplify differences in colour and compress the information. These procedures make it easier and quicker for algorithm image processing.

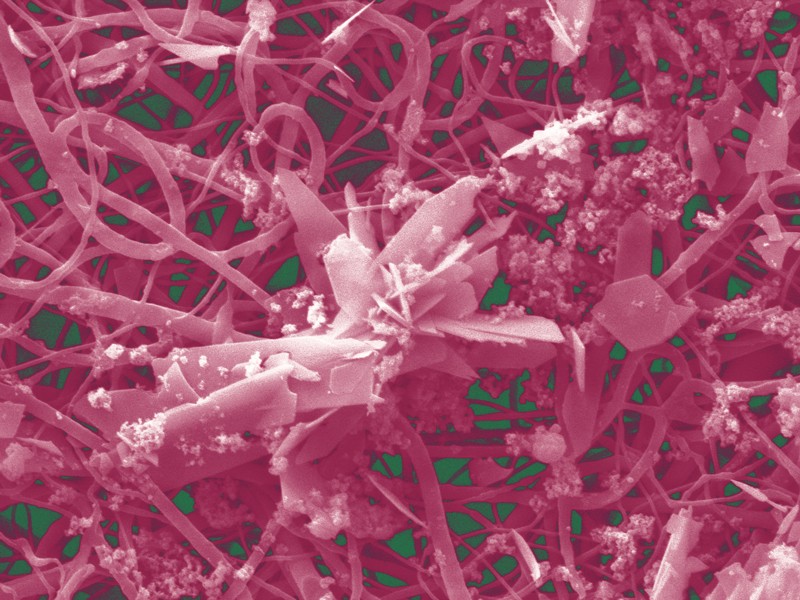

Texture is another unique organ quality. The small intestine is covered with small finger-like projections called villi. The projections increase the surface area of the organ, improving nutrient absorption into the blood stream. These villi give a particular ‘velvet-like’ texture to the images, and this texture can be singled out using a technique called Local Binary Patterns. This works by comparing each pixel’s intensity to its neighbours’, to determine whether these are larger or smaller in value than its own. For each pixel, a final number is then worked out which gauges whether an edge is present or not (see image).

Classification is the last and most important step in the whole process. At this point the software needs to decide if an image is part of the stomach, small intestine, or large intestine. To help automatically identify images, the program is trained to link the factors described above with the different organ types by being shown a small subset of images. This data is known as the training set. Once trained, the software can then automatically classify new images from different patients on its own. The software developed by the biomedical engineers was tested first by classification based just on colours or texture, then testing both features together. Factoring both in gave the best results.

“The software is still at the research stage. That research needs to be turned into a software package for a hospital’s day-to-day examinations”

After the images have been labeled, the algorithm can draw the boundaries between digestive organs. With the boundaries in place, the specialist can focus on the small intestine. At the press of a button countless hours and cash are saved.

The software is still at the research stage. That research needs to eventually be turned into a software package for a hospital’s day-to-day examinations. In the future, the algorithm could possibly be inserted directly onto the capsule. An intelligent capsule would be born creating a recording process capable of adapting to the needs of the doctor. It would show them just what they want to see.

Ideally the doctor would have it even easier with the software highlighting diseased areas automatically. The researchers at the University of Malta want to start automatically detecting abnormal conditions and pathologies within the digestive tract. For the specialist, it cannot get better than this.

The result? A shorter and more efficient screening process that could turn capsule endoscopy into an easily accessible and routine examination. Shorter specialist screening times would bring down costs in the private sector and lessen the burden on public health systems. Michael would not need to worry any longer; he’d just pop a pill.

* Michael is a fictitious character

[ct_divider]

The author thanks Prof. Thomas Attard and Joe Garzia. The research work is funded by the Strategic Educational Pathways Scholarship (Malta). The scholarship is part-financed by the European Union — European Social Fund (ESF) under Operational Programme II — Cohesion Policy 2007–2013, ‘Empowering People for More Jobs and a Better Quality of Life’