A multi-disciplinary life

Winner of the National Book Council’s award for Best Novel Loranne Vella has enjoyed an eclectic career, spanning literature, teaching, translation, and theatre, then circling back to literature again. But as Teodor Reljić discovers, her journey across creative modes had its roots at the University of Malta.

It’s not every year that the National Book Council dishes out its annual Best Novel Award to a work of time-hopping speculative fiction. But that’s exactly what happened last December, when Loranne Vella won the award for her novel Rokit (Merlin Publishers), which details the journey of Petrel, a Croatian youth who travels to Malta in search of his family roots, only to find an island ravaged by climate change.

‘With Rokit, Loranne Vella distinguished herself with another prize-winning novel that crosses genre boundaries between adult and young adult fiction,’ wrote National Book Council Chairman Mark Camilleri.

Such a dense and knotted work suggests hard creative labour, which Vella confirms, pointing out that the novel took five years to put together. But one shouldn’t assume that Rokit was all that commanded Vella’s attention in those years, nor that writing is her only chosen pursuit. In fact, she says the process left her hankering to return to performance.

‘I was interested in merging my two artistic passions and experimenting with various possibilities,’ Vella says, explaining how this want led to the Barumbara Collective in 2017, ‘which focuses on collaboration with artists from different spheres.’

As it happens, Vella being awarded the Book Council prize directly coincided with a Barumbara Collective project—the multi-disciplinary performance Verbi: mill-bieb ’il ġewwa.

And while Verbi certainly had a role to play in refreshing Vella’s creative muscles in the here and now, it also channelled key elements of her past experience. The Barumbara Collective is only the latest iteration of Vella’s involvement in the performing arts. The still-active Aleateia Theatre Group was her first and most significant project, beginning as a student project in 1992 and resulting in a generous number of experimental performances held at the Valletta Campus Theatre throughout the nineties and noughties. Vella performed, trained other actors, and documented the group’s progress.

The Barumbara project brought more deep-seated memories back to the fore. ‘With Verbi, I wanted to involve university students from the Department of Digital Arts and the Department of Theatre Studies, seeing how the project was an interdisciplinary one where visual arts, performance and literature come together in one performative installation. I can truly say I was amazed by the hard work done by the students who collaborated. Their enthusiasm reminded me of myself as a student back in the 90s.’

Vella’s own student enthusiasm did not come as immediately as all that, however. While she is now secure in her three-pronged role as writer, performer, and translator (also acknowledging her former role as a lecturer), forging an early path as a student meant first squinting through the fog.

‘It took me quite a while to figure out which were the right subjects for me,’ Vella confesses. ‘Before ‘91, I had spent a year struggling as a BCom student. This course was definitely not for me, contrary to what my teachers and counselor advised me at the time. Before that, I had registered for the one-year-long Foundation Course at university, intended for students like me who couldn’t make up their mind… for a while I was even considering Law…’

It was then that Vella learned about the Theatre Studies Programme, though a couple of years still had to pass for her to take the leap.

‘I guess I finally decided to choose what I was interested in, rather than think too much about what my future profession or career should be.’ The choices in question were Theatre Studies and English, subsequently opting to specialise in Theatre until she finished her MA in 2000.

‘Everything about me, since then, revolves around these two disciplines: theatre and literature.’

These pursuits became an active part of student life for Vella, who loves to turn her passions into more tangible projects. Vella collaborated with fellow Aleateia member Simon Bartolo in establishing Readers & Writers, a literary journal which featured original prose, poetry, and literary criticism. Running for five editions, the journal sowed the seeds for Vella’s future literary output.

‘I was still writing in English back then. It took me almost ten years to start writing stories again, this time in Maltese.’

The breakthrough came in 2004, when Vella began writing the first chapters of what would eventually become Sqaq l-Infern, the first volume of the It-Triloġija tal-Fiddien, together with Simon Bartolo. Like Rokit, the trilogy would be published by Merlin Publishers, and it managed to hit a fresh nerve in the local literary circuit.

Aimed at young readers, the trilogy proved to be a ‘Harry Potter moment’ for the Maltese literary scene. Gr

aced with eye-catching covers by renowned illustrator Lisa Falzon, its mix of local folklore and coming-of-age yarn was met with excitement and healthy sales. The trio was completed by the novels Wied Wirdien (2008) and Il-Ġnien tad-Dmugħ (2009).

‘By the time the third volume came out, Fiddien had a huge following,’ Vella remembers, observing how the trilogy also marked her first shift from theatre to literature. Another influence on this decision was her move to Luxembourg to work as a translator at the European Parliament. The next step in her literary output came in the form of MagnaTMMater, a young adult work of dystopian science fiction published in 2011.

But there was yet another step in the interim to all this—Vella’s stint as a lecturer. For five years, she taught at the University of Malta’s Department of Theatre Studies. ‘This gave me the satisfaction of examining this reality from the opposite side, working with students while keeping in mind the difficulties I had encountered myself.’

Vella had cut her pedagogical teeth much earlier. Right after graduating with a BA Hons in Theatre Studies, Vella taught Drama and English Literature at St Aloysius College. ‘Although I had not studied to become a teacher—it was the last profession I had in mind—I had the right background to teach these two subjects. After a few years at the college, I was teaching only the literature part of the English courses, and I also became responsible for directing the annual school concerts, which became bigger and more ambitious every year,’ Vella says, adding that her time as a teacher left her with many ‘proud moments’.

‘The best of these was perhaps the mobilisation of almost the entire body of students to put up a large scale performance—with orchestra, choir, side-acts, chorus, intermezzo, and all.’

Vella is keen to credit her alma mater with the results of this varied career. She has no trouble stating that ‘everything is connected, and there is a clear connecting line between my years at university and everything else I’ve done since.’

Which begs the question: what advice would she give to current University of Malta students, especially those interested in working in multiple disciplines?

‘Be passionate about the courses you follow. Experiment, explore, be curious. Ask many questions and strive to find answers. Do not just study. Discover. And make that discovery your own.’

The Philosophy of Creativity

In this age of specialisation, finding a niche is key to most people’s career progression. But it is not the only way. Cassi Camilleri sits down with philosopher poet Prof. Joe Friggieri to gain insight into his creative process.

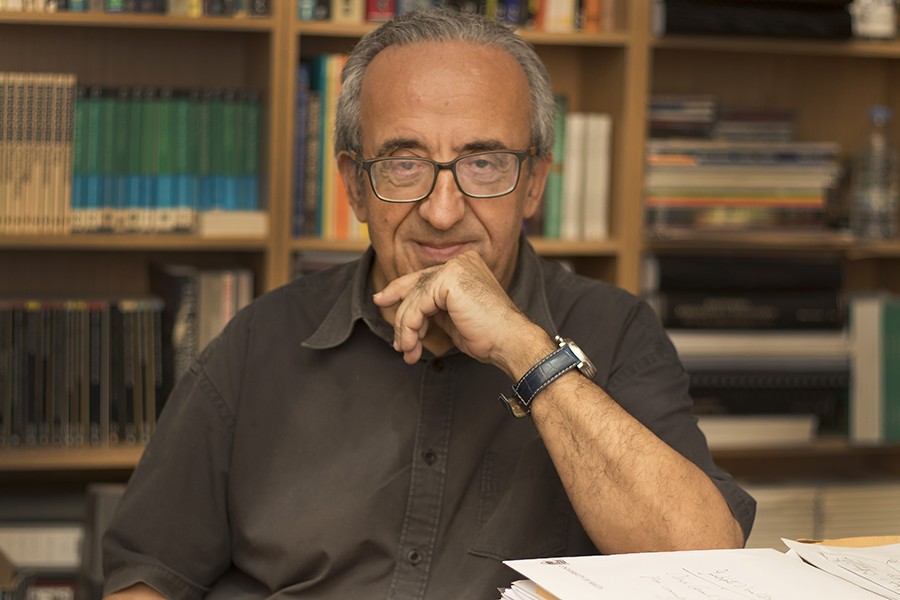

It was a very warm April day when I found myself sitting in front of Prof. Joe Friggieri. My heart was racing—I had just run up three flights of stairs for a rescheduled meeting after having missed our first earlier in the day. I had lost track of time while distributing magazines around campus. My eyes briefly scanned his library, wishing it was mine, then got right down to the business of asking questions.

Friggieri balances between two worlds: the academic and the creative. His series Nisġa tal-Ħsieb, the first history of philosophy in Maltese, is compulsory reading for philosophy students around the island. His collections of poetry and short stories have seen him win the National Literary Prize three times. I ask Friggieri if he separates his worlds in some way. ‘I can’t stop being a philosopher when I’m writing a short story or play. Readers and critics of my work have pointed that out in their reactions,’ he says. ‘I do not necessarily set out to make a philosophical point in my output as a poet, short-story writer, or playwright, but that kind of work can still raise philosophical issues.’

‘Dealing with matters of great human interest—such as love or the lack of it, happiness, joy and sorrow, the fragility of human relations, otherness, and so on—in a language that is markedly different from the one used in the philosophical analysis of such topics can still contribute to that analysis by creating or imagining situations that are close to the experiences of real human beings,’ Friggieri illustrates.

The urge to write

In reality, Friggieri is usually inspired by day-to-day moments, things normally overlooked in today’s loud and busy world. ‘In my literary works, I am inspired by what I see, hear, and feel; by people and events, by what I read about and by what I can remember,’ he says. It could be anything from a news item to a painting, a whiff of cigarette smoke, a piece of music, or a word overheard at a party. ‘All of that can trigger off an idea. Then, when I’m alone, I seek to elaborate the thought and to convey it to others by means of an image or series of images in a poem, or as part of the plot in a short story or play.’

While on the subject of inspiration and starting points, I wondered: how does Friggieri work? First, he swiftly explains his aversion to using computers for his writing. ‘I do all my writing the old-fashioned way,’ he notes. ‘I use pen and paper. I find it much easier to write that way than on my computer. It feels like my thoughts are taking shape literally as I push my pen from left to right across the page. I think with my pen, much in the same way that a concert pianist thinks with her fingers and a painter with her brush. It’s that kind of feeling that makes me want to go on writing.’ At this point, the subject of the Muse comes up. Is this something Friggieri believes in? ‘Waiting for the Muse to inspire you is just a poetic way of saying you need to have something to write about and you’re looking to find the right way of expressing it,’ Friggieri explains. ‘I write when I feel the urge or the need to write,’ he tells me with a smile.

The sheer volume of work Friggieri has built up over the years seems to imply that he writes daily. But in reality, his workflow is more akin to sprints than a marathon. He tells me deadlines are a good motivator for him to write, providing a tangible goal he can work towards. ‘My first two collections of short stories were commissioned as weekly contributions to local newspapers,’ Friggieri says. ‘That’s how ‘Ir-Ronnie’ was born.’ Ir-Ronnie is a man who finds himself overwhelmed by life’s pressures: family, work and everything in between. As he starts to lose touch with reality, ‘ordinary, everyday living becomes an ordeal for him, an obstacle race, a struggle for survival,’ says Friggieri. More recent works, such as his latest collections of short stories—Nismagħhom jgħidu and Il-Gżira l-Bajda u Stejjer oħra—also reflect this realism, exploring the complexity of interpersonal relations between different people from different walks of life. On the other hand, Ħrejjef għal Żmienna (Tales for Our Times) finds its roots in magical realism, which makes these stories a very different experience for his readers. The books have been well received, with translations into English, French, and German. Paul Xuereb, who worked on the English translation, described the tales as ‘drawing on the dream-world and waking reveries to suggest the ambiguity and often vaguely perceived reality of our lives.’

The Creative Philosopher

When it comes to talking about his other works and creativity, Friggieri often refers to language. When I asked him about his thoughts on creativity and whether he believed everyone to be ‘creative’, his response was positive. ‘As human beings, we are all, up to a point and in some way, creative,’ he says. A prime example is humanity’s use of language. ‘Think of the way we use language. Dictionaries normally tell you how many words they contain, but there’s no way you can count the number of sentences you can produce with those words. Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules. In a very real sense, every individual uses language creatively, in a way that is very much his or her own. I think the best way to understand what creativity is all about is to start from this very simple fact.’

Language enables us to be creative in that sense, because we can use it whichever way we like, to communicate our thoughts and express our feelings freely, without being bound by any definite set of rules.

Is Friggieri creative when he writes his philosophical papers? ‘Yes,’ he nods. ‘Each kind of writing has its own characteristic features. But creativity is involved in all of them.’ With philosophy, ‘you need more time,’ he notes. ‘You need to know what others have said about the subject, so it involves researching the topic before you get down to saying what you think about it. When it comes to writing a poem or play, you’re much freer to say what you like, much less constrained.’

In fact, Friggieri has five plays under his belt. Here is where the two worlds of academia and creative writing merge. ‘In three of my five full-length plays, I make use of historical characters (Michelangelo, Caravaggio, Socrates) to highlight a number of issues in ethics and aesthetics that are still very much alive today,’ says Friggieri. Taking L-Għanja taċ-Ċinju (Swansong) as an example, Friggieri explains how ‘Socrates defends himself against his accusers by raising the same kind of moral issues one finds in Plato’s Apology. The Michelangelo and Caravaggio plays, on the other hand, highlight important questions in aesthetics, such as the value of art, the relation between art and society, the presence of the artist in the work, the difference between good and bad art, and the mark of genius.’

Talking of theatre, Friggieri remembers how, before writing his first play, he had directed several performances. This was where he learnt the trade and what it meant to have a good production. ‘I have also had the good fortune of working with a group of dedicated actors from whom I learnt a lot. In my view, one should spend some time working in theatre before starting to write for it.’

As time was pressing, and the sun was starting to move away from its opportune place in the window, I asked Friggieri one last question, the one I had been obviously itching to ask. What advice does he have for writers? The answer I got was one I should have expected. ‘Budding writers should write. Then they should show their work to established practitioners in the field. The first attempts are always awkward. As time goes by, one learns to be less explicit and more controlled, to use images to express one’s thoughts where poetry is concerned, to develop an ear for dialogue if one is writing a play, to produce well-rounded characters in a novel, construct interesting plots, and so on. All this takes time, but it will be worth the effort in the end.’ And with that, we had the perfect closing.

Author: Cassi Camilleri