Each type of review serves a unique purpose in bringing us closer to understanding the complexities of research and each type requires following a certain methodology. Choosing the right type of review depends on your needs and goals. There are various online tools which you may use to help you make that decision, such as Right review - online tool or a simple flow chart created by the Louisiana State University Library.

In case of any questions, feel free to consult your lecturer or contact the Library.

This type of review provides a comprehensive overview of published literature on a specific topic. It doesn't have to follow a strict search or appraisal strategy. The main purpose of the narrative review is to provide readers with the summary and synthesis of ideas on a specific subject, without adding any new contributions. It may be used to establish a current level of knowledge on a particular topic or identify research gaps, however, since it relies on the author's interpretation of the literature it can be biased and not as comprehensive as other review methods.

This type of review follows a rigorous protocol to identify, select, evaluate, synthesise and analyse high-quality evidence. It minimises bias and ensures a reliable summary of existing research on a particular subject. Systematic reviews are usually performed by a team of subject specialists with at least two of them screening retrieved literature. The search should be exhaustive, covering multiple databases, registers, and grey literature. Due to their comprehensive nature, these types of reviews are usually most time consuming.

This approach combines elements of both a systematic review and a narrative review. It incorporates elements of a systematic search and evaluation of literature, however it is not as rigorous as a systematic review and does not need to follow a strict protocol. It still provides a balanced and comprehensive perspective on the topic and is usually undertaken when working on dissertations.

As the name suggests, this type of review prioritises speed. Cochrane defines a rapid review as “a form of knowledge synthesis that accelerates the process of conducting a traditional systematic review through streamlining or omitting specific methods to produce evidence for stakeholders in a resource-efficient manner” (Garritty et al., 2021).

Rapid review is perfect when you need timely insights, especially in rapidly evolving fields. It is usually used to evaluate new or emerging topics and to summarise what is already known on the subject. In contrast to the systematic reviews, which typically take from 6 to 24 months to be completed, rapid reviews often reach completion within 5 to 12 weeks.

It is important to note that the exact duration of a rapid review can vary considerably based on adjustments made to the process and specific goals and needs of researchers.

Rapid reviews typically apply systematic review methods to search for literature, although with a less strict approach. They also incorporate various methodological adaptations aimed at speeding up the process and ensuring timely completion. Due to a less strict approach, rapid reviews are less comprehensive and more prone to bias than systematic and scoping reviews and explanations for shortcuts and subsequent limitations should be explicitly reported and justified.

Scoping Review maps out the available literature to identify key concepts, sources, and gaps. It's like creating a roadmap for future research endeavours. Usually a scoping review would be performed prior to conducting more extensive literature review. The extent of the research is dependent on available time.

Scoping review still needs to apply some steps of the systematic review process, such as framing the research question, identifying and selecting relevant studies (which should be done by more than one person to eliminate the bias), charting the data and summarising and reporting the findings by adhering to specific guidelines, it does not require appraisal of the evidence.

Find out more about scoping review methodology.

JBI Scoping Review Methodology: manual and protocol template.

Umbrella Review gathers evidence from multiple systematic reviews on a similar topic. Hence, it is placed at the top of the hierarchy of evidence, above systematic reviews. Due to the explosion in the number of systematic reviews being published, various systematic reviews may produce different conclusions or solutions to a particular problem. An Umbrella Review is undertaken to assess the methodology of previously conducted systematic reviews and/or summarise what is known or remains unknown and needs to be explored further. It's a way to see the big picture and draw conclusions based on existing systematic reviews. This type of review is optimal for conducting a network meta-analysis since multiple comparators for a specific treatment/therapy can be simultaneously compared.

Learn more about umbrella reviews.

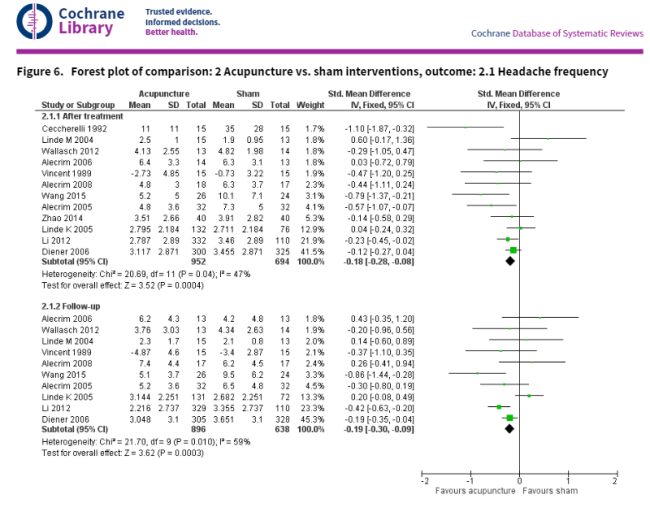

If you ever explored the subject of systematic reviews, most probably you heard about meta-analysis. Meta-Analysis may form a part of a systematic review by statistically combining data from multiple studies and presenting them all together, typically in the form of a forest plot to visualise the aggregated effect amongst multiple studies. An example of a forest plot is shown below:

Linde, K., Allais, G., Brinkhaus, B., Fei, Y., Mehring, M., Vertosick, E. A., Vickers, A., & White, A. R. (2016). Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016(6), CD001218.

https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub3

In the figure above, two separate meta-analyses are depicted, stacked on top of each other. The first, labelled as 2.1.1, illustrates the effects of acupuncture versus sham interventions immediately after treatment.

The second, labelled as 2.1.2, represents the effects of acupuncture versus sham interventions at follow-up. To ensure consistency, the outcomes (mean and standard deviation) were transformed into standardised mean differences, along with their respective 95% confidence intervals. They utilised a fixed-effects model to compile this meta-analysis. The choice between a fixed or random effects model depended on the heterogeneity among the studies. A fixed-effect model assumes a single true effect size underlies all studies in the meta-analysis, hence the term "fixed effect." In contrast, the random-effects model assumes that the true effect may vary from study to study due to differences (heterogeneity) among studies.

For further guidance, we recommend consulting your lecturer or a statistician. You can also find more information in this article.

On the left-hand side of the image, you'll find the author and year of publication for each study. Moving to the right, you'll see the mean, standard deviation (SD), and the total number of participants who received acupuncture in each study. Further to the right, you'll find the mean, standard deviation (SD), and the total number of participants who received the sham intervention. The number of participants in each study is presented as a percentage of the total number of participants in all the studies, providing a weighted score. For instance, the study by "Ceccherelli 1992," which had only 30 participants, contributes just 1.7% to the total, while the study by"Diener 2006," with 625 participants, contributes a substantial 41.5% to the meta-analysis. The sum of these percentages equals 100%. The statistical software, such as RevMan, computes the standardised mean difference, and typically, the researcher can select which effect size to use and present.

Finally, on the right-hand side of the image, you'll find the forest plot. This plot visually represents each standardised mean difference and its 95% confidence interval. For example, in "Ceccherelli 1992," a negative standardised mean difference is displayed to the left of the vertical line (the line of no effect), while the standardised mean difference for "Linde M 2004" is on the right side of the vertical line, indicating a positive effect. The size of the green dot within each confidence interval corresponds to the number of participants (weighed in %) in each study, meaning larger studies have larger green dots/squares. Larger studies also tend to have narrower 95% confidence intervals, reflecting greater precision due to their larger sample size.

At the bottom of the forest plot, you'll find the meta-analytic effect size presented as a black diamond. This represents the weighted average of the results from all the studies. In this case, since the diamond does not cross the vertical line (the line of no effect), the result of the current meta-analysis is considered statistically significant (p<0.05). The p-value for this meta-analysis was p=0.0004. For additional guidance, we recommend consulting your lecturer. The forest plot under subheading 2.1.2 Follow-up provides another meta-analysis, which can be interpreted in a similar manner.

Amog, K., Pham, B., Courvoisier, M., Mak, M., Booth, A., Godfrey, C., Hwee, J., Straus, S. E., & Tricco, A. C. (2022). The web-based “Right Review” tool asks reviewers simple questions to suggest methods from 41 knowledge synthesis methods. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; J Clin Epidemiol, 147, 42-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.03.004

Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Dettori, J. R., Norvell, D. C., & Chapman, J. R. (2022). Fixed-Effect vs Random-Effects Models for Meta-Analysis: 3 Points to Consider. Global Spine Journal, 12(7), 1624-1626. https://doi.org/10.1177/21925682221110527

Fusar-Poli, P., & Radua, J. (2018). Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evidence-Based Mental Health; Evid Based Ment Health, 21(3), 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300014

Garritty, C., Gartlehner, G., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., King, V. J., Hamel, C., Kamel, C., Affengruber, L., & Stevens, A. (2021). Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 130, 13-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal; Health Info Libr J, 26(2), 91-108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Linde, K., Allais, G., Brinkhaus, B., Fei, Y., Mehring, M., Vertosick, E. A., Vickers, A., & White, A. R. (2016). Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2016(6), CD001218. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub3

Plante, H. (2023, Sep 6,). Systematic, scoping, and rapid reviews: An overview. Simon Fraser University. Retrieved Nov 7, 2023, from https://www.lib.sfu.ca/about/branches-depts/rc/writing-theses/writing/literature-reviews/systematic-scoping-rapid-reviews

Randa Lopez, M. (2023, Sep 11,). Systematic Reviews: What Type of Review is Right for You? Louisiana State University. Retrieved Nov 7, 2023, from https://guides.lib.lsu.edu/c.php?g=872965&p=7860555

Reardon, D. (2006). Doing Your Undergraduate Project (1st ed.). London: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849209076

Samnani, S. S., Vaska, M., Ahmed, S., & Turin, T. C. (2017). Review Typology: The Basic Types of Reviews for Synthesizing Evidence for the Purpose of Knowledge Translation. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan; J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 27(10), 635-641. https://hydi.um.edu.mt/permalink/f/1rh358i/TN_cdi_proquest_miscellaneous_1954410260

Compiled by:

Agata Scicluna Derkowska - Senior Assistant Librarian, University of Malta.

Emanuel Schembri - Visiting lecturer at the Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Malta.

Last updated: 17 Nov, 2023