Conducting database searches for any type of literature reviews requires constructing a comprehensive search strategy tailored for each database. Well designed searches are crucial to locate all relevant literature on the subject.

It's crucial to keep track of all fields and filters applied to ensure that your search is replicable.

It is advisable to keep a copy of your search strategy and files with database search results, ideally in the RIS format, for future use, such as when updating the review or if a peer reviewer requests an update. This is essential for the sake of reproducibility and transparency. For guidance on how to report the search within a systematic review, please refer to PRISMA-S.

Developing a well defined research question is a crucial part of conducting a systematic review (or any type of review). This question will form the basis of your work, helping you identify the concepts that will come in handy when you build your search strategy.

Using a framework in formulating a research question is crucial. Frameworks provide a structure for the search strategy and help in identifying key terms for each component of the question.

One of the most commonly used frameworks is PICO:

PICO stands for:

P: Population/Patient – Who is the population or group of interest?

I: Intervention – What is the intervention or exposure?

C: Comparison – What is the alternative or comparison (if applicable)?

O: Outcome – What is the outcome or effect you are measuring?

Example: Is low-fat diet more effective than standard diet in reducing cholesterol levels in adults with high cholesterol?

P (Population): Adults with high cholesterol

I (Intervention): Low-fat diet

C (Comparison): Standard diet

O (Outcome): Reduction in cholesterol levels

PICO framework might not always suit all types of questions however, there are other frameworks which you can apply, for example for qualitative studies.

PEO stands for:

P: Population

E: Exposure

O: Outcome

Example: Does cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) reduce symptoms of depression in elderly individuals?

P (Population): Elderly individuals

E (Exposure/Intervention): Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

O (Outcome): Reduction in symptoms of depression

SPIDER stands for:

S: Sample/ Population

PI: Phenomenon of Interest – What topic, issue, or experience will you explore?

D: Design – What research design or approach you will use to collect data?

E: Evaluation – What is the outcome or result that is being evaluated or understood?

R: Research type – Qualitative, or quantitative, or mixed?*

Example: What are the experiences of nurses in managing stress during the COVID-19 pandemic?

S (Sample): Nurses

PI (Phenomenon of Interest): Managing stress during the COVID-19 pandemic

D (Design): Semi-structured interviews

E (Evaluation): Understanding nurses' experiences and coping strategies

R (Research type): Qualitative

*Qualitative- seeks to understand participants' experiences, perceptions, and behaviour.

Quantitative - focuses on numerical data and analysing it using statistical methods. Mixed method - combines both qualitative and quantitative research methods within a single study.

These are just a few frameworks available. Whichever one you select, keep in mind that a well-defined question serves as the pathway to a successful search.

Find out more about frameworks.

Once you have formulated a research question and identified the key concepts, the next step entails identifying potential keywords/synonyms and subject headings which can be used to locate relevant materials.

Developing a successful search strategy involves a considerable amount of testing. At times, even a minor change in a single keyword can lead to change in search results, for example searching randomised controlled trials vs randomized controlled trials.

Keywords are individual words or short phrases that are directly related to the topic you're researching. They are often taken from the title, abstract or full text of a paper. Using keywords allows for a broader search and enables you to discover a range of materials that might be relevant to your subject.

Subject headings, also known as controlled vocabulary, are standardised terms assigned to resources by librarians or indexers, for example MeSH terms in PubMed /Medline /Cochrane /CINAHL databases and Emtree in Embase database. These terms come from a predefined list of terms that represent specific concepts. Subject headings ensure consistency and precision in searching because they categorise materials under established terms, making it easier to find related information. Subject headings provide a more focused and structured way to explore a topic and help you retrieve materials specifically relevant to your research.

Using a combination of keywords and subject headings can enhance the effectiveness (sensitivity and precision) of your search strategy.

Typically, your first set of keywords will be already included in your research question.

Let’s use our PICO question as an example:

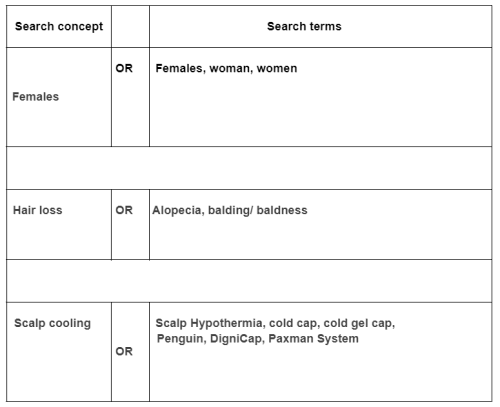

Does scalp cooling (intervention), compared to scalp compression (comparison), effectively reduce hair loss (outcome) in females undergoing chemotherapy (population)?

Keywords: scalp cooling, scalp compression, hair loss, females, chemotherapy

If you're new to the subject, it may be easier to start with simpler keywords. These keywords can be used to search through resources like the Library catalogue (HyDi), Google Scholar, or other databases. Taking the time to review titles and abstracts will provide insight into the terminology used by authors. Additionally, both library catalogues and databases typically offer item records that showcase additional keywords or subject headings associated with the publication.

To further explore subject headings, you can use the MeSH terms browser (for medical subject headings) the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH) browser. For example, a proper medical subject heading describing hair loss is alopecia. These MeSH terms can be used in PubMed and Medline.

Some databases, like CINAHL or EMBASE, might implement their own subject headings. On the other hand, databases such as Web of Science or Scopus might not use them at all. While certain databases may require customisation of search strategies, you will consistently employ the same set of keywords across all of them.

Using multiple keywords is essential to build an effective search string. There are several different ways on how you can combine all of your search terms.

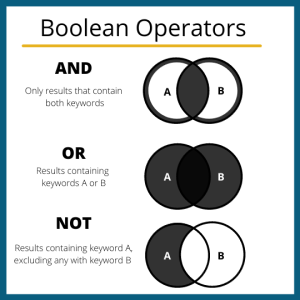

Boolean Operators (AND, OR, NOT):

Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT) are crucial for refining searches. Make sure to always enter these operators in uppercase letters.

AND: Use AND to narrow results and retrieve all terms in the records.

Example: hair loss AND chemotherapy will retrieve records combining both of these keywords together within one paper

OR: Use OR to broaden the search by connecting synonyms or other related terms.

It is especially useful when using multiple words to describe a single concept within your research query.

Example: hair loss OR alopecia

When combining multiple concepts in your search query, make use of parentheses ().

Example: (hair loss OR alopecia) AND chemotherapy

NOT: Apply NOT to exclude terms. Example: female NOT male.

Vetter, C. (2021, Feb 19). Diagram Explaining Boolean Operators. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved Nov 23, 2023, from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Diagram_Explaining_Boolean_Operators.png#metadata

Searching for a Phrase:

At times, using multiple adjacent words as keywords can lead to irrelevant outcomes.

For instance, searching for papers using the keyword stress management might generate articles like "The management of stress-strain state of the bases for stabilising uneven settlements." While both words are present in the title, they may not be retrieved as we intended them to be, providing results not related to our research topic.

To guarantee the retrieval of the exact phrase, enclose it within quotation marks.

For example: "stress management". However one must also consider including "stress-management" since the hyphen within " " can yield different results.

Use of quotation marks can work differently depending on the database being used. It is important to familiarise yourself with the functions of each database you plan to search prior to applying them.

In PubMed, each keyword search automatically retrieves matching MeSH terms and truncated words. Using quotation marks in PubMed allows one to retrieve the exact term without expanding it to MeSH terms, and it can be used for both, a single word or a phrase.

In EBSCO databases, enclosing search terms with quotation marks, such as "pain management," will retrieve the words in the exact order and form as written.

In Scopus, quotation marks are used to retrieve a loose or approximate phrase, which means plurals and spelling variants will be included. To find the exact phrase in Scopus, enclose the phrase in curly brackets { }.

Truncations:

Use truncation symbol - asterisk (*) - to search for various forms of a word.

Example: cultur* finds culture, cultural, etc.

Remember to place the asterisk at the end of the core of the word; otherwise, it will not work correctly.

Many databases and search engines offer advanced search options that can help you further refine your search. In addition to the techniques already mentioned, you can also consider narrowing your search to specific fields, such as the title or abstract.

Furthermore, advanced search also allows for the application of various limiters or filters, such as publication type, publication date, language of the publication, discipline etc. Subject specific databases might offer unique filters that further assist in refining your search.

There are specific filters that you can use to further refine your search for a concept, idea, or study design. These filters can be included in your search strategies. Special filters typically consist of a series of predefined free-text terms, text words, phrases, and subject headings. They have already been developed to help you find literature related to your specific concept, idea, or study design of interest within a particular database or platform.

You can use specially designed and tested search filters where appropriate. However, do not use filters in pre-filtered databases. For example, do not use randomised trial filters in the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials.

More on special filters.

Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Search Filters Database.

Ameen, J. (2023, Oct 26,). Systematic Reviews: 4. Search Terms & Strategies. University of California, Merced. Retrieved Nov 7, 2023, from https://libguides.ucmerced.edu/systematic-reviews/search-terms

Booth, A., Noyes, J., Flemming, K., Moore, G., Tunçalp, Ö, & Shakibazadeh, E. (2019). Formulating questions to explore complex interventions within qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Global Health; BMJ Glob Health, 4, e001107. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001107

Cantrell, S. (2023, Sep 19,). Systematic Reviews: 2. Develop a Research Question. Duke University. Retrieved Nov 7, 2023, from https://guides.mclibrary.duke.edu/sysreview/question

Chesne, A. D. (2023, Jul 14,). Evidence-Based Practice: PICO and SPIDER. Charles Sturt University. Retrieved Nov 7, 2023, from https://libguides.csu.edu.au/ebp/pico_and_spider

Glanville, J., Lefebvre, C., Manson, P., Robinson, S., Brbre, I. & Woods, L. (2023, Sep 24,). Systematic Reviews: Filters. ISSG Search Filter Resource. Retrieved Nov 7, 2023, from https://sites.google.com/a/york.ac.uk/issg-search-filters-resource/home?authuser=0

Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R., & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research; BMC Health Serv Res, 14(1), 579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

University of Malta Library. (2023, HyDi help. L-Università ta' Malta. Retrieved Nov 7, 2023, from https://www.um.edu.mt/library/help_az/hydihelp/

Compiled by:

Agata Scicluna Derkowska - Senior Assistant Librarian, University of Malta.

Emanuel Schembri - Visiting lecturer at the Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Malta.

Last updated: 11 June, 2025